Twentieth Century Ireland

1923 AD – 2000 AD | From Free State to Republic and the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

From Free State to Republic

Following the Irish Civil War, while the Irish Free State was self-governing, it was not a fully independent republic. Over the following decades, political leaders worked to gradually dismantle the remaining constitutional ties to Britain. Éamon de Valera, a key figure in the anti-treaty movement, became the dominant political force on his return to power and his party, Fianna Fáil, incrementally removed the symbols of British authority. The oath of allegiance to the British monarch was abolished and the office of Governor-General was removed. The last step in this process was the passing of the Republic of Ireland Act in 1948, which came into effect in 1949 and formally declared Ireland a republic, finally severing all constitutional links with Britain and leaving the Commonwealth.

The Troubles in Northern Ireland

Meanwhile, in Northern Ireland, which had opted to remain part of the United Kingdom, a period of sustained political and sectarian conflict began in the late 1960s. This period, known as "The Troubles", lasted for three decades. The conflict was primarily fought between two sides:

- Unionists/Loyalists: Predominantly Protestant, they supported Northern Ireland's continued place in the United Kingdom.

- Nationalists/Republicans: Predominantly Catholic, they sought to unite Northern Ireland with the Republic of Ireland.

The conflict was characterised by a mix of political unrest, civil rights protests and widespread violence carried out by paramilitary groups on both sides, including the Provisional IRA and loyalist paramilitaries. The British Army was also a central player. The Troubles caused thousands of deaths and left deep scars on Northern Irish society, scars that are still visible today. The conflict finally came to an end with the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, which established a power-sharing government and a framework for peace.

The Irish Free State

The Irish Free State was the political entity that governed 26 of Ireland's 32 counties from its establishment following the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1922 until its replacement by the sovereign state of Ireland in 1937. It was a turbulent period of consolidation, economic struggle and political realignment, largely due to the immediate aftermath of the Civil War and the ongoing political divisions it created.

Consolidation of the New State

The first task of the new Free State government was to win the Irish Civil War and establish its authority. Led by W. T. Cosgrave, the Provisional Government, and later the Executive Council, created a national army to defeat the anti-treaty forces. The victory in the civil war secured the state's existence but created a lasting political divide. Following the conflict, the government worked to build the institutions of the new state, including a police force (Garda Síochána), a civil service and an independent judiciary. This process was largely successful, demonstrating that the Irish could govern themselves effectively.

Cumann na nGaedheal and Fianna Fáil Governments

The political landscape of the Free State was dominated by the two factions that emerged from the Civil War.

- Cumann na nGaedheal was the party of the pro-treaty side. It governed the Free State from 1922 to 1932. Their primary focus was on political and economic stability. They established the foundational institutions of the state, maintained law and order and pursued a cautious economic policy focused on agriculture and trade with Britain. While successful in building a functional state, their conservative policies and association with the harsh measures of the Civil War made them unpopular with some sections of the population.

- Fianna Fáil, led by Éamon de Valera, was formed in 1926 by the anti-treaty faction. De Valera and his party initially refused to take their seats in the Dáil due to the oath of allegiance to the British monarch. They eventually entered the Dáil in 1927 after modifying the oath. Their main goal was to dismantle the remaining ties to Britain imposed by the Anglo-Irish Treaty. In 1932, Fianna Fáil won a majority and de Valera became head of government. His rise to power marked a major turning point, as he began to introduce policies that would lead to a complete break from the British Commonwealth.

Economic Challenges and Social Development

The Free State faced significant economic and social challenges. The economy was heavily reliant on agriculture, which struggled with low prices and competition. The state also had to pay a substantial amount to Britain in land annuities, a debt from the Land Acts of the late 19th century. De Valera's government, in an act of defiance, stopped these payments, leading to the Anglo-Irish Trade War (or "Economic War") of the 1930s.

Socially, the new state was conservative and Catholic. The Church's influence was considerable, affecting legislation on issues such as divorce, censorship and education. Despite the economic difficulties, there were notable developments. The Shannon Scheme, a major hydroelectric power plant completed in 1929, was a landmark engineering project that provided electricity to much of the country and symbolised the nation's progress. However, high emigration rates, particularly among young people, persisted throughout this period, reflecting the limited economic opportunities at home.

The Free State effectively came to an end in 1937 with the adoption of a new constitution (Bunreacht na hÉireann), which removed all references to the British monarch and established the modern sovereign state of Ireland.

Éire and the Republic of Ireland

The period between 1937 and 1949 saw the Irish state complete its break from the United Kingdom, culminating in its formal declaration as a republic. This transformation was largely driven by Éamon de Valera and his government.

The Constitution of Ireland

Following his election in 1932, Éamon de Valera set about cutting the remaining ties to Britain imposed by the Anglo-Irish Treaty. His ultimate goal was to replace the Irish Free State with a new, fully sovereign state. In 1937, he introduced Bunreacht na hÉireann, which was passed by a national referendum.

This new constitution:

- Renamed the state from the Irish Free State to Éire (the Irish word for Ireland).

- Abolished the office of Governor-General and replaced it with an elected President of Ireland.

- Claimed sovereignty over the entire island of Ireland, including Northern Ireland, in Articles 2 and 3.

- Established a new system of government with a Taoiseach (Prime Minister), a Dáil (lower house), and a Seanad (upper house or Senate).

Crucially, the 1937 Constitution removed the last formal references to the British monarch and British law, though the state remained a member of the British Commonwealth.

Neutrality during WWII ("The Emergency")

As World War II loomed, Éamon de Valera declared that Ireland would remain neutral. This policy, known as "The Emergency" in Ireland, was a powerful assertion of the nation's new-found sovereignty. The decision to remain neutral was controversial and strained relations with both Britain and the United States.

De Valera's government pursued a policy of strict neutrality, which involved:

- Refusing to provide Britain with the use of the "Treaty Ports" which had been returned to Ireland in 1938. This decision was a major point of contention with Britain and the United States, as it hindered Allied naval operations in the Atlantic.

- Interning German and Allied servicemen who crashed or landed in Ireland.

- Censoring news reports to prevent either side from gaining a propaganda advantage.

Despite the official neutrality, there was a degree of tacit cooperation with the Allies, particularly in the sharing of meteorological information. The policy of neutrality was deeply popular at home, as it reinforced the sense of independence and allowed Ireland to avoid the devastating destruction of the war.

Declaration of the Republic (1949)

The final step in Ireland's journey to full sovereignty was taken by the inter-party government of John A. Costello. In 1948, the government introduced the Republic of Ireland Act, which was passed in law and came into effect on 18th April, 1949.

This Act:

- Declared that Éire was a republic.

- Formally repealed the 1936 External Relations Act, which had been the last remaining link to the British Crown.

- Removed Ireland from the British Commonwealth.

This declaration brought Ireland's constitutional evolution to a close, completing the journey from a British dominion to a fully sovereign and independent republic. In response, the British Parliament passed the Ireland Act of 1949, which acknowledged the Republic of Ireland but also guaranteed that Northern Ireland would remain part of the United Kingdom for as long as its parliament wished. This action solidified the partition of the island.

The Celtic Tiger: Ireland's Economic Revolution

For much of the 20th century, Ireland was one of Western Europe's poorest nations, defined by economic stagnation and the persistent challenge of emigration. Yet, in a few short decades, it transformed itself from a quiet agricultural society into a vibrant, high-tech economy known as the "Celtic Tiger". This journey was driven by a pivotal shift in economic policy, membership in the European community and a strategic embrace of globalisation.

Emigration and Stagnation

In the 1950s, Ireland's economy was in a dire state. Decades of protectionist policies, designed to foster self-sufficiency, had resulted in an uncompetitive industrial sector. The nation remained overwhelmingly dependent on agriculture and high unemployment was rampant.

The most significant social consequence of this economic failure was mass emigration. Lacking opportunities at home, hundreds of thousands of Irish citizens left, primarily for the United Kingdom, the United States and Australia. This wasn't just a loss of people; it was a "brain drain" that stripped the country of its young, ambitious and often most educated individuals. The population declined, and a sense of national malaise set in, casting a long shadow over the young republic.

The Move Towards Liberalisation (1950s-70s)

Recognising that protectionism had failed, the government initiated a radical change in direction, in the late 1950s. The First Programme for Economic Expansion, launched in 1958 under the guidance of visionary civil servant T.K. Whitaker, dismantled trade barriers and actively sought to attract foreign investment.

Key policies included:

- Tax Incentives: Offering tax holidays and low corporate tax rates to foreign companies.

- Industrial Development Authority (IDA): Empowering this state agency to aggressively court multinational corporations, particularly from the US, in sectors like pharmaceuticals, engineering and electronics.

- Free Trade: The Anglo-Irish Free Trade Agreement of 1965 was a crucial step, opening up Ireland's largest export market and preparing it for broader European integration.

This shift laid the critical groundwork for future growth by connecting Ireland to the international economy and beginning the process of industrial modernisation.

Joining Europe: The EEC

Ireland's entry into the European Economic Community (EEC), the forerunner to the European Union, in 1973 was a transformative moment. Membership provided three main benefits:

- Market Access: It gave Irish exporters tariff-free access to a vast European market, reducing the country's historic over-reliance on the British market.

- Common Agricultural Policy (CAP): Billions of pounds flowed into Ireland through the CAP, modernising the agricultural sector, increasing farm incomes and dramatically improving rural life.

- Structural and Cohesion Funds: From the 1980s onwards, EU funds helped finance massive upgrades to Ireland's infrastructure, including roads, telecommunications and educational institutions.

EEC membership anchored Ireland within Europe, boosted national confidence and provided the capital and market access necessary for economic take-off.

The Roar of the Celtic Tiger

By the 1990s, all the pieces were in place. A convergence of factors unleashed a period of unprecedented, explosive growth known as the "Celtic Tiger".

The key drivers were:

- Foreign Direct Investment (FDI): A low 12.5% corporate tax rate made Ireland the premier European destination for US tech giants like Intel, Microsoft, Dell and Google, who established their European headquarters there.

- An Educated Workforce: Decades of investment in free secondary and third-level education had produced a young, skilled, English-speaking workforce perfectly suited to the needs of these high-tech firms.

- EU Single Market: Full access to the European single market, established in 1992, amplified the benefits of EEC membership.

- Social Partnership: A series of national agreements between the government, trade unions and employers kept wage inflation in check, ensuring stability and competitiveness.

The results were stunning. Ireland's GDP growth soared, consistently topping European charts. For the first time in its modern history, the country experienced net immigration, as young Irish people returned home and foreign nationals arrived to fill jobs. A massive construction boom transformed the skylines of Dublin and other cities. This economic boom also fueled social change, leading to increased secularism, multiculturalism and a surge in national self-confidence.

Northern Ireland and The Troubles

The Troubles were a period of intense sectarian conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted for three decades. The conflict was primarily between Nationalists / Republicans, who were predominantly Catholic and sought a united Ireland, and Unionists / Loyalists, who were predominantly Protestant and wanted to remain part of the UK. The roots of the conflict can be traced back to the 17th century with the plantation of Ulster, but the modern era began in the late 1960s.

The Civil Rights Movement and the Escalation of Violence

The conflict's modern phase was ignited by a civil rights movement in the late 1960s. Inspired by movements in the US, Catholic Nationalists began protesting against decades of institutionalised discrimination. They highlighted issues such as gerrymandering (the manipulation of electoral boundaries to ensure a Unionist majority), unequal access to housing and discrimination in employment. Prominent figures in this movement included John Hume, a co-founder of the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP), and Bernadette Devlin, a young and fiery socialist activist.

These peaceful protests were often met with violent opposition from Unionist counter-protesters and the police force (the Royal Ulster Constabulary). This violence, coupled with the British government's failure to address the underlying issues, led to a rapid escalation of violence.

Paramilitary groups on both sides, such as the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA), the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and the Ulster Defence Association (UDA), began to carry out bombings, shootings and assassinations. The British Army was deployed in 1969 to restore order but soon became a central actor in the conflict, often seen by Nationalists as an occupying force.

Divergent Outcomes

- Bloody Sunday (1972): A peaceful civil rights march in Derry turned into a massacre when British paratroopers shot and killed 14 unarmed civilians. This event, which sparked international condemnation, galvanised support for the IRA and marked a significant turning point in the conflict.

- Internment (1971–1975): The British government's policy of internment without trial, which was almost exclusively used against Catholic Nationalists, further alienated the Catholic community and fueled a surge in paramilitary recruitment.

- The Hunger Strikes (1981): A series of hunger strikes by Republican prisoners, led by Bobby Sands, sought to regain "Special Category Status" as political prisoners. Sands was elected as a Member of Parliament during his strike. He and nine other prisoners starved themselves to death, drawing global attention and making Sands an icon for the Republican movement.

- The Anglo-Irish Agreement (1985): Signed by British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and Taoiseach (Irish Prime Minister) Garret FitzGerald, this agreement gave the Republic of Ireland a consultative role in Northern Ireland's affairs. It was a significant step towards internationalising the conflict and infuriated Unionists.

The Good Friday Agreement: A Turning Point

After years of secret negotiations and peace efforts, a breakthrough was finally achieved. The Good Friday Agreement was a landmark peace deal signed on 10th April, 1998. It established a new power-sharing government in Northern Ireland, the Northern Ireland Assembly, which mandated that both Nationalists and Unionists participate in decision-making.

Key political figures who played crucial roles in the peace process included:

- John Hume (SDLP) and David Trimble (Ulster Unionist Party), who were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1998 for their efforts.

- Gerry Adams, the leader of Sinn Féin, the political wing of the IRA, who led his party's transition from an abstentionist party to a major player in the peace process.

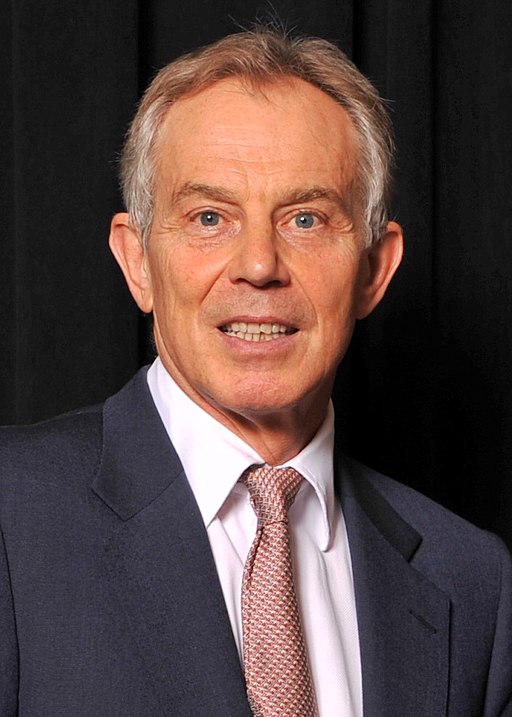

- British Prime Minister Tony Blair and Taoiseach Bertie Ahern, who were instrumental in the final stages of the negotiations.

- US Senator George Mitchell, who chaired the talks and was praised for his impartiality and patience.

The agreement largely ended the large-scale violence of The Troubles, although sporadic sectarian incidents continue to occur. It provided a framework for a peaceful political future, recognising the right of the people of Northern Ireland to identify as Irish, British or both, and establishing cross-border institutions.

Sources & Further Reading

The information on this page is compiled from established archaeological and historical research. For detailed reading, please consult the following sources:

- Economic history of the Republic of Ireland (Wikipedia).

- Ireland: Changing Times (Ask About Ireland).

- Contemporary Ireland (ResearchGate).

- CRS Report: Northern Ireland Peace Process (Congress.gov).

- Northern Ireland Peace Process (Wikipedia).

- Strengths & Weaknesses of the Good Friday Agreement (EduBirdie).

- The Belfast Agreement (Good Friday Agreement) (Parliament UK).

- Power-Sharing in Northern Ireland (NI Assembly Education).

- UK Parliament Northern Ireland Affairs Committee Report.

- About the Good Friday Agreement (Ireland.ie DFA).

- The DUP and Power-Sharing Return to Northern Ireland (Global Policy Watch).

- CRS Report: Devolved Government and Policing (EveryCRSReport.com).

- Good Friday Agreement: Decommissioning (Gov.ie Dept. of Justice).

- Good Friday Agreement (Wikipedia).

- Devolution and Belfast Good Friday Agreement Challenges (Consoc.org.uk).

- 2024 Reestablishment of Devolved Government (Congress.gov).

- UK's Withdrawal and Power-Sharing Institutions (Congress.gov).

- The Windsor Framework and DUP Deal (Institute for Government).

- Ireland and the EU: A Mutually Beneficial Relationship (IDA Ireland).

- Celtic Tiger and 2008 Financial Crisis (Wikipedia).

- Post-2008 Irish Economic Downturn (Wikipedia).

- Irish Economy Expansion and Recession (Wikipedia).

- Ireland's Strong Recovery from Global Financial Crisis (Economics Observatory).

- Post-2008 Irish Economic Downturn - Full Article (Wikipedia).

- Ireland's Engagement with the EU (Ireland.ie).

- Ireland's EU Membership Benefits (European Commission).

- Ireland's Adoption of the Euro (European Commission).

- Foreign Direct Investment in Ireland (NZ MFAT).

- Role of Foreign Direct Investment in Ireland (SteeringPoint).

- Multinational Enterprise Relocation (IMF eLibrary).

- OECD Global Minimum Corporate Tax (Emerald Insight).

- Ireland's Population and Immigration Trends (Famworld).

- Ireland's Transformation to a Multicultural Society (Famworld).

- Census 2022: Irish and Non-Irish Citizenship (CSO).

- Ireland's Challenges as a Dynamic Nation (Famworld).

- Direct Democracy and Constitutional Demise (Oxford Academic).

- Irish Abortion Referendum "Repeal the 8th" (Georgetown Global Irish).

- Divided Attitudes to Church in Ireland (CruxNow).

- The Catholic Church, State, and Society in Ireland (JCFJ).

- Ireland's Gaeltachts and Irish Language Revival (IrishCentral).

- Irish Language (Gaeilge) (Wikipedia).

- Irish Language Revival: A Modern Renaissance (Medium).

- Languages of Ireland Guide: Gaelscoileanna (Eirin.co).

- Irish Army (Wikipedia).

- Ireland's Continuous UN Peacekeeping Missions (Oireachtas).

- Ireland's Peacekeeping Policy and Triple Lock (Ireland.ie DFA).

- Ireland's Official Development Assistance Programme (Gov.ie DFA).

- Irish Aid's Focus Areas (IFPRI).

- Irish Aid Funding Approaches (Gov.ie DFA).

- Irish Aid Priority Sectors (Gov.ie DFA).

- Irish Aid International Development Priorities (Gov.ie DFA).

- Irish Foreign Policy: Human Rights (Gov.ie DFA).

- Ireland's International Priorities (Ireland.ie DFA).

- Foreign Relations of Ireland (Wikipedia).

- Irish Government Position on Military Neutrality (Muse JHU).

- Ireland's UN Security Council Term (Gov.ie DFA).

- How Brexit Affects Irish Businesses (Eurodev).

- Trade in Goods under the Northern Ireland Protocol (QUB).

- The Protocol Ensures No Hard Border (Parliament UK).

- Northern Ireland Protocol: Original Alignment (Wikipedia).

- Financial Times: GB to NI Trade Border (Taylor & Francis Online).

- Northern Ireland Protocol: Trade Border in Irish Sea (Wikipedia).

- Brexit Impact on Irish Agriculture and Food (IIEA).

- Brexit: UK as Landbridge for Irish Exports (Copenhagen Economics).

- Brexit: Border and Customs Challenges (Eurodev).

- Brexit's Long-Term Economic Impact on Ireland (Copenhagen Economics).