A Century of Upheaval

The early modern era in Ireland witnessed drastic changes driven by England's renewed ambition for complete control. From the mid-16th century, Irish society was reshaped by the sowing of the seeds of sectarian division through the Protestant Reformation, massive land dispossession during the aggressive Plantations and a long struggle of escalating religious conflict.

The English Reformation created a deep religious divide, as the vast majority of Irish Gaelic and Old English populations remained steadfastly Catholic in defiance of the Protestant English Crown. This split became a core element of future political resistance.

To solidify control and enforce conformity, the English initiated systematic Plantations: the confiscation of Irish lands and their resettlement with Protestant English and Scottish colonists. These schemes aimed to establish loyal, compliant communities and dismantle the traditional Irish order.

The combination of imposed religion and land seizure ignited fierce and brutal conflict. Rebellions and wars, marked by extreme violence, led to further widespread land confiscations and the eventual entrenchment of a Protestant ruling class over a dispossessed Catholic majority.

The Reformation in Ireland

The changes of the Protestant Reformation in England, initiated by Henry VIII's break with Rome, were not contained by the Irish Sea. From the mid-16th century, the English Crown began a determined effort to impose its religious changes upon Ireland. The assertion of the Kingdom of Ireland in 1541 coupled with sustained attempts to impose Protestantism, was met with widespread and resolute resistance from the Catholic population.

Henry VIII and the Kingdom of Ireland

Prior to Henry VIII, English rule in Ireland was nominally a "Lordship", a territory held by the English monarch often perceived as a feudal overlordship granted by the Pope. With Henry VIII's Act of Supremacy in 1534, this medieval arrangement became untenable.

To align Ireland with his new ecclesiastical authority and assert complete sovereignty, the Irish Parliament was coerced into passing the Crown of Ireland Act in 1541. This act declared Henry VIII and his successors to be King of Ireland. This seemingly legalistic change was significant: it unilaterally severed any remaining ties to papal authority in Ireland and formally integrated Ireland into the English Crown's Protestant realm, at least in statute. This provided the legal basis for the subsequent religious changes.

Attempts to Impose Protestantism

With the legal framework established, successive English monarchs pursued the imposition of the Church of Ireland, a Protestant institution modelled on the Church of England. The methods employed were varied but often lacked the necessary resources, consistent application or genuine appeal to the populace.

- Acts of Supremacy and Uniformity: Irish Parliaments were pushed to pass Acts of Supremacy (acknowledging the monarch as head of the Church) and Acts of Uniformity (mandating the use of the Book of Common Prayer and attendance at Anglican services). These laws, however, were largely unenforceable outside The Pale.

- Dissolution of Monasteries: Irish monasteries, significant centres of Catholic religious life, learning and local influence, were dissolved. Their lands and wealth were confiscated by the English, enriching the royal coffers but further alienating the Catholic population.

- Appointment of Protestant Clergy: Protestant bishops and clergy were appointed to Irish dioceses and parishes. However, many struggled to gain acceptance. They often lacked fluency in the Irish language, faced hostile congregations and frequently found their churches empty, with local people preferring clandestine Catholic services.

Resistance from the Catholic Population

Despite the efforts of the English, the vast majority of the Irish population remained devoutly Catholic. Their resistance was multifaceted:

- Deep-Rooted Faith: Catholicism was deeply embedded in Irish culture, social structures and personal identity. The transition from a local, oral tradition to a state-controlled, foreign-language liturgy was alienating.

- Language Barrier: As noted, many Protestant clergy could not preach in Irish, making their message inaccessible.

- Political and Religious Fusion: For the Irish, adhering to Catholicism became intertwined with loyalty to their traditional way of life and resistance to English political domination. To be Catholic was to be Irish; to be Protestant was to be English. This fusion strengthened both national and religious identity.

- Counter-Reformation Influence: From the continent, the Catholic Counter-Reformation provided vital support. Priests trained in European seminaries, returned to Ireland, often at great personal risk, to minister to the Catholic population and reinforce their faith. This intellectual and spiritual backbone helped sustain resistance.

The English Crown's attempts to impose Protestantism largely failed, creating a lasting and bitter religious divide that would be the basis of future conflicts and rebellions. Religious difference became a key component of Irish society, transforming political and land grievances into a holy war.

Reshaping the Landscape: The Irish Plantations

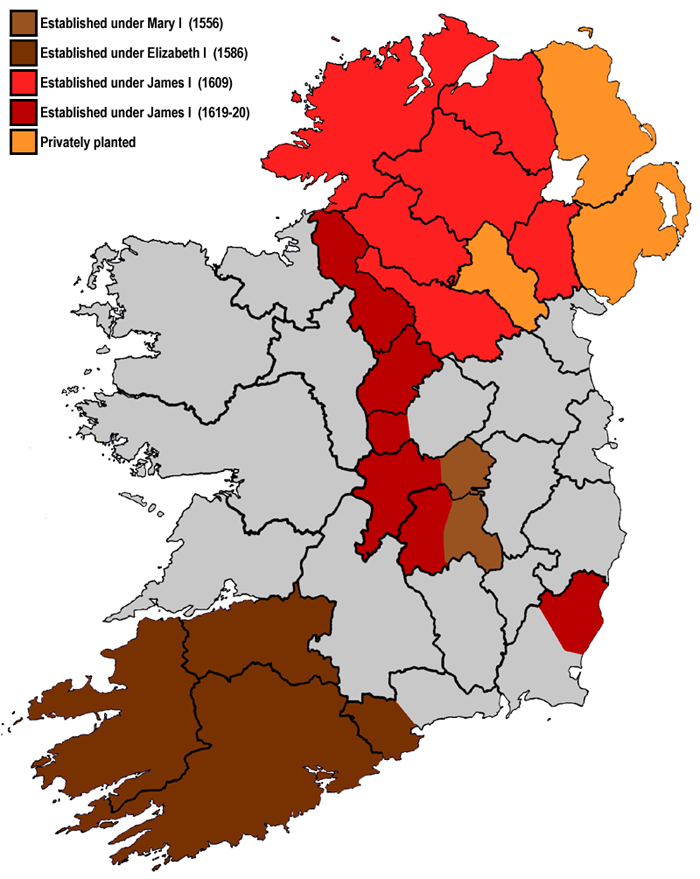

Following the failure of the Reformation to secure control through religious conformity, the English Crown turned to a more direct and physically transformative strategy: the Plantations. This systematic policy involved the confiscation of vast tracts of land from dispossessed Irish owners and their resettlement with loyal, predominantly Protestant, colonists from England and Scotland. These initiatives reshaped Ireland's demography, economy, social structure and political allegiances.

Mary I's Leix and Offaly Plantation

The concept of plantation as a means of controlling Ireland was not new, but it gained official state sponsorship in the mid-16th century. The first major attempt was initiated under Queen Mary I (a Catholic monarch, ironically, highlighting that early plantations were driven more by control than pure religion). In 1556, lands belonging to the Gaelic clans of Ó Mordha (O'Moore) of Laois (Leix) and Ó Conchobhair Faly (O'Connor Faly) of Offaly were confiscated after prolonged resistance to English authority.

These territories were shired (divided into counties) and renamed Queen's County (Laois) and King's County (Offaly), in honour of Mary and her husband Philip II of Spain. The native Irish were forcibly removed or displaced and the land was granted to English settlers, who were expected to build fortifications and introduce English farming methods. While somewhat limited in scale and often facing ongoing resistance from displaced clans, this plantation served as a crucial template for future, much larger, undertakings.

The Ulster Plantation

The most ambitious and ultimately, the most consequential of all the Irish plantations was the Ulster Plantation, initiated by James I in 1609. This followed the decisive defeat of the Gaelic lords Hugh O'Neill and Red Hugh O'Donnell in the Nine Years' War and their subsequent flight to continental Europe in 1607 (The Flight of the Earls), which left huge plots of land in Ulster vacant and ripe for confiscation.

- Scale and Scope: Six entire counties in Ulster - Armagh, Cavan, Coleraine (later Derry), Donegal, Fermanagh and Tyrone - amounting to approximately 3.5 million acres, were declared English property. These lands were then carefully parcelled out to "undertakers" (English and Scottish landowners who undertook to plant settlers), "servitors" (former English soldiers) and a small number of "deserving Irish".

- Demographic Transformation: Thousands of Protestant Scottish Presbyterians and English Anglicans migrated to Ulster, altering the region's demographic balance and creating a lasting Protestant majority in parts of Ulster, in contrast to the rest of Ireland.

- Economic Development: The planters introduced new farming techniques, established towns, built roads and developed industries like linen manufacturing. This led to significant economic growth in the planted areas, but it also displaced and marginalised the Irish.

- Social Stratification: A new, rigid social hierarchy emerged, with Protestant settlers at the top, holding land and political power and the dispossessed Catholic Irish relegated to the bottom, often as tenants on their former lands, labourers or living in poverty.

- Lasting Legacy: The Ulster Plantation created the distinct Ulster Protestant identity and laid the historical roots for the sectarian divisions and political conflicts that would trouble the north for centuries. It remains arguably the most impactful single event in shaping modern Ulster.

Other Plantations and Their Consequences

While Ulster was the largest, other significant plantations occurred across Ireland:

- Munster Plantation (from 1580s): Following the Desmond Rebellions, vast lands in Munster were confiscated and offered to "undertakers", particularly from the West Country of England. This plantation aimed to create a loyal Protestant buffer in the south, but it was less comprehensive and often faced more sporadic resistance than Ulster.

- Wicklow Plantation (from 1620s): Aimed at subduing the unruly O'Byrne clan and securing the approaches to Dublin.

- Cromwellian Plantation (1650s): This was the most brutal and sweeping of all. Following the Cromwellian conquest, there were huge seizures of land across almost every county in Ireland, particularly from Catholic landowners, both Gaelic and Old English. The infamous policy of "To Hell or Connaught" saw many Irish Catholics forcibly removed from their ancestral lands and resettled in the barren west of Connacht, while their former properties were granted to Cromwellian soldiers and adventurers. This plantation solidified the Protestant Ascendancy and fundamentally dispossessed the Catholic landowning class.

The cumulative effect of these plantations:

- Massive Land Dispossession: By the end of the 17th century, Catholic land ownership in Ireland had plummeted from over 90% before the plantations to less than 15%.

- Emergence of a Divided Society: They cemented a rigid social and economic hierarchy based on religion and ethnicity, with a Protestant landlord class and a Catholic tenantry.

- Source of Future Conflict: By creating a dispossessed native population and a privileged settler class, the plantations laid the foundations for future rebellions, land agitation and sectarian conflict. They were not merely land transfers but an attempt at radical social engineering.

Wars and Rebellions in Early Modern Ireland

From the mid-16th to the early 17th century there was a period of relentless warfare and rebellion in Ireland. Driven by increasingly aggressive policies of religious imposition (the Reformation) and land confiscation (the Plantations) from the English. Powerful Gaelic chieftains and even Old English lords rose in desperate resistance. These conflicts were brutally suppressed, leading to massive devastation, further land dispossession and ultimately, the complete dismantling of the old Gaelic order.

The Desmond Rebellions

The Desmond Rebellions represent the first major wave of armed Catholic and Gaelic resistance. These were two distinct phases of uprising in the province of Munster, primarily led by the powerful FitzGerald Earls of Desmond (a leading Old English family, but one that had become heavily Gaelicised).

- Context: The rebellions were sparked by a combination of factors: the expansion of English government influence into Munster, attempts to impose Protestantism, the establishment of the Munster Presidency (a new English administrative body) and the growing threat of a comprehensive Munster Plantation, which directly challenged the traditional power and landholdings of the Desmond Geraldines and their Gaelic allies.

- Conflict: The first rebellion (1569-1573) was a reaction to English administrative impositions and attempts to curb the Earl's power. The second (1579-1583), more widespread and brutal, was fueled by religious fervor and the arrival of a small Papal-sponsored force. Both rebellions saw immense destruction, targeting civilian populations and agricultural land.

- Outcome & Significance: The rebellions were ruthlessly crushed by English forces. The ferocity of the suppression led to widespread famine and depopulation across Munster, with one contemporary account estimating 30,000 deaths from starvation in six months. The most significant outcome was the confiscation of over 500,000 acres of Geraldine land, which became the basis for the large-scale Munster Plantation in the 1580s. This set a grim precedent for future English policy: complete military conquest followed by extensive land dispossession.

The Nine Years' War and the Battle of Kinsale

The Nine Years' War, also known as Tyrone's Rebellion, was the most formidable challenge the English faced in Ireland. It pitted the might of England against a powerful alliance of Gaelic Irish chieftains, led by the astute and charismatic Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone, and Red Hugh O'Donnell of Tyrconnell, the last great Gaelic lords.

- Context: Ulster, the last bastion of independent Gaelic Ireland, remained largely untouched by English direct rule and plantations. O'Neill and O'Donnell sought to maintain their traditional autonomy and defend their Catholic faith against English encroachment. They skillfully forged a pan-Gaelic alliance and even secured military and financial support from Catholic Spain.

- Conflict: The war was characterised by fierce campaigning, with early Irish victories demonstrating the effectiveness of O'Neill's reformed army. However, England, committing unprecedented resources, eventually gained the upper hand. The war culminated in the decisive Battle of Kinsale (1601). Spanish forces, sent to aid O'Neill, landed in Kinsale, Co. Cork. O'Neill and O'Donnell marched south to link up with them, but their combined forces were decisively defeated by the English army.

- Outcome & Significance: Kinsale was a crushing blow to the Irish confederacy. Though the war dragged on for two more years, ending with O'Neill's submission in 1603, the defeat effectively broke the back of organised Gaelic resistance. It paved the way for the total conquest of Ulster and marked the end of the traditional Gaelic military order.

The Flight of the Earls

The final, symbolic act signaling the demise of the old Gaelic order was the Flight of the Earls in 1607. Just four years after the end of the Nine Years' War, Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone and Rory O'Donnell, Earl of Tyrconnell (Red Hugh's brother), along with nearly one hundred other leading Ulster Gaelic chieftains, their families and followers, boarded a ship at Lough Swilly and sailed for continental Europe.

- Reasons for Flight: The Earls felt increasingly constrained by English administration in Ulster. They feared arrest, the imposition of English law and the systematic confiscation of their remaining lands for the burgeoning Ulster Plantation. They likely hoped to gain renewed Spanish or Papal support for a future return and rebellion, though this never materialised.

- Significance: The Flight of the Earls was a symbolic event. It meant that the last great Gaelic lords, who had maintained an unbroken line of chieftainship for centuries and fought for Gaelic independence, had left their homelands. Their departure created a power vacuum and, critically, left their vast lands entirely open to confiscation by the English on grounds of treason. This enabled the full and unhindered implementation of the Ulster Plantation, permanently altering the demography and political landscape of Northern Ireland and marking the definitive end of the traditional Gaelic aristocratic order.

These successive wars and rebellions led to the near-complete destruction of the old Gaelic political system, massive land transfers to Protestant settlers and the deepening of religious and ethnic divisions.

Confederate Ireland and the Cromwellian Conquest

The mid-17th century plunged Ireland into a period of unprecedented trauma, driven by a combination of religious intolerance, political upheaval and land grievances. What began as a desperate uprising by the Irish against escalating oppression evolved into a devastating eleven-year conflict known as the Irish Confederate Wars, culminating in the brutal Cromwellian Conquest of Ireland (1649-1653), which inflicted immense devastation and cemented mass land confiscation, epitomised by the chilling policy of "To Hell or to Connacht".

The Spark Ignites: The 1641 Rebellion and the Irish Confederate Wars

The volatile mix of religious tension, the Plantations and political insecurity for Catholics under a Protestant-dominated Parliament in England reached a boiling point in October 1641. Fears of further confiscations and a complete suppression of Catholicism, coupled with the instability arising from the deepening constitutional crisis between King Charles I and the English Parliament, led to a widespread Gaelic rebellion in Ulster.

The rebellion rapidly spread, drawing in both the dispossessed Gaelic Irish and many of the "Old English" Catholic lords. By 1642, these Catholic factions formed the Confederate Association of Ireland, establishing a de facto Catholic government based in Kilkenny. "Confederate Ireland" sought to secure religious freedom for Catholics and roll back the Plantations.

The ensuing Irish Confederate Wars (1641-1653) were a complex, multi-sided conflict involving:

- Confederate Catholics (Gaelic and Old English)

- Royalists (primarily Old English Catholics)

- Parliamentarians (English Protestant forces)

- Scottish Covenanters in Ulster

- Various independent Irish forces

Allegiances shifted constantly, leading to a fragmented and prolonged war that devastated the countryside and exhausted all parties.

Cromwell's Conquest

The arrival of Oliver Cromwell and his highly disciplined New Model Army in August 1649 marked a new, brutal and decisive phase of the wars. Fresh from victory in the English Civil War and the execution of King Charles I, Cromwell's Parliamentarian regime viewed the Irish rebellion not just as a political uprising, but as a wicked Catholic insurgency and a direct threat to the newly formed English Republic.

Cromwell's campaign was characterised by swift, ruthless military action and a complete lack of mercy for those who resisted. His most infamous acts include the massacres at:

- Drogheda (September 1649): After a siege, Cromwell's forces stormed the town. Virtually the entire garrison (including English Royalists and Irish Catholics) and many civilians were put to the sword. Cromwell justified this as God's righteous judgment and a deterrent against further resistance.

- Wexford (October 1649): A similar massacre followed, with soldiers and civilians killed after the town was taken.

These events, and others like them, were deliberate acts of terror designed to break Irish resistance. Cromwell's forces systematically crushed remaining opposition across the country, pursuing a scorched-earth policy that left immense devastation in its wake. Towns were razed, crops destroyed and the population decimated by both conflict and famine.

Land Confiscation and "To Hell or to Connacht"

The most profound and lasting consequence of the Cromwellian Conquest was the unprecedented scale of land confiscation and forced demographic restructuring. The English Parliament aimed to punish the Irish rebels, pay off its soldiers and financial "adventurers" who had funded the war and secure English Protestant control over Ireland once and for all.

The vast majority of Catholic landowners were deemed "delinquent" or "rebels". Their lands were confiscated under the Act for the Settlement of Ireland (1652).

The notorious policy, famously encapsulated by the phrase "To Hell or to Connacht", dictated the fate of these dispossessed landowners. They were given the choice: submit to death if they refused to comply or be forcibly removed from their ancestral lands in the east and centre of Ireland and transplanted to the barren province of Connacht by a specific deadline. Those who failed to move were often executed.

This policy represented the largest and most systematic land transfer in Irish history. By 1660, Catholic land ownership in Ireland had plummeted from approximately 60% before 1641 to roughly 8-9%. The confiscated lands were parcelled out to Cromwellian soldiers in lieu of pay, and to the funders of the war.

The Cromwellian conquest resulted in massive loss of life and a complete socio-economic upheaval.

The Williamite War and the Penal Laws

The close of the 17th century brought one final, devastating conflict to Ireland, directly linked to a seismic shift in English dynastic politics. The Williamite War (often called the War of the Two Kings) was fought on Irish soil, with lasting consequences. Its conclusion, marked by the Treaty of Limerick, saw promises quickly broken, leading directly to the systematic oppression embodied by the Penal Laws, which impacted the lives of Irish Catholics for over a century.

The Glorious Revolution and James II's Flight to Ireland

The catalyst for the Williamite War lay in England's "Glorious Revolution" of 1688. When King James II, a devout Catholic, faced growing opposition from the Protestant establishment, his Protestant daughter Mary and her Dutch Protestant husband, William of Orange, invaded England. James II's support collapsed, and he fled to France.

From the perspective of Irish Catholics, James II was their last hope for religious tolerance and a reversal of the Cromwellian land settlements. Thus, in March 1689, James II landed in Kinsale. He hoped to use Ireland as a base to reclaim his British throne, starting the Williamite War. His Irish Catholic supporters became known as Jacobites.

The Decisive Clash: The Battle of the Boyne and the Siege of Limerick

The ensuing war was fought between the Jacobite forces loyal to James II, and the Williamites (a diverse army of English, Scottish, Dutch, Danish, Huguenot and Ulster Protestants) loyal to William of Orange.

- Battle of the Boyne (July 12, 1690): This was the pivotal engagement of the war, fought near Drogheda. King William III himself led his forces against James II's army. Despite both kings being present, it was not the bloodiest battle but a strategically decisive victory for the Williamites. James II fled Ireland shortly after the battle, though the Jacobite resistance continued under the leadership of Patrick Sarsfield. The Battle of the Boyne became a potent symbol of Protestant triumph and is still commemorated today, particularly by Ulster Loyalists.

- Siege of Limerick (1691): After a failed siege in 1690, Williamite forces, now under General Ginkel, returned to besiege the heavily fortified city of Limerick, the last major Jacobite stronghold. Despite a heroic defense led by Sarsfield, the city eventually succumbed to defeat in October 1691.

The Treaty of Limerick and Its Aftermath

The fall of Limerick brought an end to the major hostilities. The Treaty of Limerick, signed on the 3rd of October, 1691, officially ended the Williamite War and contained significant provisions for the surrendering Jacobite forces and the Catholic population:

- Military Terms: Jacobite soldiers who wished to continue fighting for James II were allowed to sail to France (the "Flight of the Wild Geese", leading to many Irish serving in continental armies). Those who stayed could return home.

- Civil Articles: These were crucial for the Catholic population. They offered protection to Catholics in Limerick and key parts of Clare, Cork, Kerry and Sligo from forfeiture of their estates, provided they swore allegiance to William and Mary. Crucially, it also promised that Catholics would enjoy "such privileges in the exercise of their religion as they did enjoy in the reign of King Charles II", implying a degree of religious toleration.

However, these promises were swiftly and systematically broken. The Protestant-dominated Irish Parliament, eager to secure its ascendancy and further dispossess Catholics, largely ignored or reinterpreted the generous terms of the Civil Articles. This betrayal fostered deep resentment among Irish Catholics.

The Penal Laws

Following the Williamite victory and the subversion of the Treaty of Limerick, the Protestant Ascendancy (the ruling Protestant elite in Ireland) moved to secure its power and prevent any future Catholic challenge through a comprehensive system of discriminatory legislation known as the Penal Laws. These laws, enacted gradually from the late 1690s, had a devastating intent and impact on Catholics:

- Intent: To weaken the Catholic population economically, socially and politically, preventing them from ever challenging the Protestant monopoly on power. They aimed to force conversions to Protestantism, or at least render Catholics incapable of effective resistance.

-

Impact on Catholics:

- Land Ownership: Catholics were forbidden from buying land, inheriting Protestant land, leasing land for more than 31 years or even passing on their land undivided (it had to be split among all sons, fragmenting estates). This rapidly diminished Catholic land ownership, already low after Cromwell, to a mere 5% by 1778.

- Political Rights: Catholics were barred from holding any public office, sitting in the Irish Parliament, voting, entering the legal profession or serving in the army or navy.

- Education: Catholics were forbidden from operating schools, teaching or sending their children abroad for Catholic education. This aimed to deny them leadership and intellectual development.

- Religious Practice: The laws placed severe restrictions on Catholic worship, outlawing bishops, monks and friars, and registering secular priests. Building Catholic churches was restricted.

- Social & Economic Life: Catholics faced restrictions on inheriting property, acting as guardians, possessing horses over a certain value, and many other things.

The Williamite War and the subsequent Penal Laws irrevocably solidified the Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They ensured English control, entrenched sectarian division, and relegated the vast Catholic majority to a subordinate, dispossessed and disenfranchised status.

Sources & Further Reading

The information on this page is compiled from established archaeological and historical research. For detailed reading, please consult the following sources:

- Irish Georgia: Plantations.

- Ask About Ireland: Tudor Plantations.

- Oxford Academic (Past & Present): Article on Plantations.

- Ask About Ireland: Ulster Plantation - Who Gained What.

- Wikipedia: Plantations of Ireland.

- Wikipedia: Plantation of Ulster.

- Ask About Ireland: From the Plantation of Ulster.

- Ask About Ireland: Ulster Plantation / Cromwellian Settlement (Primary Students).

- Irish Genealogical & Historical Society of Missouri: Learn.

- Cambridge History of Ireland: Plantations 1550-1641.

- Irish History Show: The Desmond Rebellions.

- Wikipedia: Second Desmond Rebellion.

- Wikipedia: Second Desmond Rebellion (Quashed).

- Wikipedia (local copy): Nine Years' War (Ireland).

- EBSCO: Research Starters - Tyrone Rebellion.

- The Burkean: Fall of the House of Desmond and Plantation of Munster.

- History Reconsidered: O'Neill's Rebellion.

- Ask About Ireland: The Flight of the Earls.

- Superprof: Ireland History.

- Ó Siochrú, Micheál. God's Executioner: Oliver Cromwell and the Conquest of Ireland. Faber and Faber, 2008.

- Ó Siochrú, Micheál. Confederate Ireland 1642–1649: A Constitution of Crisis. Four Courts Press, 1999.

- Lenihan, Pádraig. Confederate Catholics at War, 1641–49. Cork University Press, 2001.

- Wheeler, James Scott. The Irish and British Wars, 1637-1654: Politics, Religion and Warfare. Routledge, 2002.

- Moody, T.W., Martin, F.X., & Byrne, F.J. (eds.). A New History of Ireland, Vol. III: Early Modern Ireland 1534-1691. Oxford University Press.

- Connolly, S.J. (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Irish History. Oxford University Press.

- National Museum of Ireland: 17th Century Collections.

- History Ireland (Homepage).

- CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts.

- Ask About Ireland: The Williamite War in Ireland.

- Wikipedia: Treaty of Limerick.

- Wikipedia: Williamite War in Ireland.

- National Army Museum: Army and Glorious Revolution.

- Orange Heritage: Anniversary of James II Landing in Ireland.

- Ask About Ireland: Narrative Notes - The Williamite War in Ireland.

- Britannica Kids: Battle of the Boyne.

- Wikipedia: Battle of the Boyne.

- Wikipedia: Battle of the Boyne (Williamite War in Ireland).

- National Army Museum: Battle of the Boyne.

- Limerick.com: Limerick - City of the Sieges.

- Limerick.ie: Treaty Stone.

- Parliament.uk: Historic Hansard - Treaty of Limerick.

- Wikipedia: Penal Laws (Ireland).

- Legal Blog Ireland: The Penal Laws.

- Britannica: Penal Laws.

- Yale Macmillan Center: History of Penal Laws Against Irish Catholics.

- Boyne Valley Day Tours: Battle of the Boyne.