Georgian and Ascendancy Ireland

1691 AD – 1800 AD | Protestant Ascendancy, limited reform and rebellion.

A System of Control and Seeds of Rebellion

The late 17th and 18th centuries in Ireland were defined by the rigid imposition of the Protestant Ascendancy, a system that solidified English power and curtailed the rights of the Catholic majority. While this era saw some limited attempts at reform, particularly from the Protestant “Patriot” movement, the deeply ingrained inequalities and the revolutionary currents sweeping across Europe culminated in a violent rebellion.

The Protestant Ascendancy: A System of Control

Following the Williamite victory and the subsequent subversion of the Treaty of Limerick, a minority Protestant elite, predominantly members of the Church of Ireland, established nearly total political, economic and social domination over Ireland. This system became known as the Protestant Ascendancy. Its authority was formalised and rigorously maintained by the Penal Laws, a comprehensive body of legislation designed to disenfranchise, impoverish and marginalise the Catholic majority.

Under the Ascendancy:

- Political Power: Only members of the Church of Ireland could hold public office, sit in the Irish Parliament, or vote.

- Land Ownership: Penal Laws drastically restricted Catholic landownership, ensuring that the vast majority of land remained in Protestant hands.

- Social and Economic Status: Catholics were barred from many professions, education and social advancement, effectively relegating them to the lowest tier of society.

This system created a very divided society, with the Protestant minority enjoying immense privilege and power, while the Catholic majority endured systematic discrimination and economic hardship.

Limited Reform and the “Patriot” Parliament

Despite the rigid nature of the Ascendancy, the latter half of the 18th century saw growing calls for reform, primarily from within the Protestant elite itself. Inspired by the American Revolution and Enlightenment ideals, a powerful parliamentary faction known as the Patriot Party, led by figures like Henry Grattan, campaigned for greater legislative independence for the Irish Parliament.

These efforts led to limited reforms:

- Legislative Independence (1782): Often referred to as "Grattan's Parliament", the Irish Parliament achieved significant legislative autonomy, effectively freeing itself from direct control by the British Privy Council and the Declaratory Act of 1719. This meant the Irish Parliament could, theoretically, make laws for Ireland without British oversight, though the British government still controlled the executive through the Lord Lieutenant.

- Catholic Relief Acts (1778-1793): Under pressure from both internal and external factors, some of the harsher Penal Laws were repealed. Catholics were gradually permitted to lease and inherit land, enter certain professions and gain the right to vote in parliamentary elections (though not to sit in Parliament) by 1793.

However, these reforms were often viewed as too little, too late and primarily benefited wealthier Catholics, leaving the majority of the population still dispossessed and disenfranchised. The “Patriot” Parliament, though more independent, remained exclusively Protestant.

Revolutionary Fervor: The 1798 Rebellion

The ideals of the American and French Revolutions, advocating for liberty, equality and republicanism, found fertile ground in Ireland, transcending traditional religious divides. This led to the formation of the Society of United Irishmen in 1791, a radical, non-sectarian organisation founded by figures like Theobald Wolfe Tone. Initially seeking parliamentary reform and Catholic emancipation, the United Irishmen, despairing of peaceful change, eventually aimed to overthrow British rule and establish an independent Irish Republic.

The government's repressive measures, including the suppression of the United Irishmen and widespread atrocities by loyalist forces, pushed the country towards open revolt. The 1798 Rebellion erupted in May, spreading across several counties. While there were significant uprisings in Wexford, Ulster and other areas, the rebellion suffered from a lack of central coordination, severe government repression and the failure of crucial French military aid to arrive at the decisive moment.

The rebellion was suppressed, leading to severe loss of life and further devastation. Its failure, paired with the British government's determination to prevent future French invasions and Catholic uprisings, directly paved the way for the Act of Union in 1800, which abolished the Irish Parliament and incorporated Ireland directly into the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from the 1st of January, 1801. This marked the formal end of the Protestant Ascendancy's independent parliamentary power, but reinforced British control over Ireland.

The Penal Laws and the Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland

The Protestant Ascendancy was meticulously upheld and enforced by a comprehensive code of discriminatory legislation: the Penal Laws. These laws were designed to dismantle Catholic power, secure Protestant dominance and ensure the unwavering loyalty of Ireland to the British Crown.

The Chains of Conformity: Details and Practical Effects of the Penal Laws

The Penal Laws, enacted incrementally from the late 1690s through the early 18th century, were a devastating legislative assault primarily aimed at the Roman Catholic majority, though they also imposed significant disabilities on Protestant Dissenters who did not conform to the established Church of Ireland. Their core intent was to force conversion to the Anglican Church or to render Catholics powerless and impoverished.

-

Land Ownership and Inheritance: This was arguably the most crippling aspect.

- Catholics were forbidden from purchasing land or inheriting land from Protestants.

- Catholic land could not be left to a single heir; it had to be divided equally among all sons, leading to the rapid fragmentation and economic unsustainability of Catholic estates (known as gavelkind clauses).

- Leases for Catholics were limited to a maximum of 31 years, discouraging long-term investment.

- Any Catholic owning a horse valued at more than £5 could have it confiscated by a Protestant offering that sum.

Practical Effect: This systematically dispossessed the remaining Catholic landowning class. By 1778, Catholic landownership had plummeted to less than 5% of the island's total, ensuring that economic power and the basis for political influence rested overwhelmingly with Protestants.

-

Political Disenfranchisement: Catholics were barred from holding any public office, from local parish vestries to government positions. They could not sit in the Irish Parliament or vote in parliamentary elections. They were also excluded from the legal professions, the military and the navy.

Practical Effect: This completely removed Catholics from the levers of power, ensuring Protestant control over all aspects of governance and law enforcement.

-

Education and Professions: Catholics were forbidden from operating schools, teaching, or sending their children abroad for Catholic education. Catholic universities were outlawed. They were also largely excluded from practicing law, medicine and other lucrative professions unless they converted.

Practical Effect: This stifled Catholic intellectual and social mobility, aiming to create an uneducated and subordinate population incapable of leadership. It also led to the growth of clandestine "hedge schools".

-

Religious Practice: While Catholic worship was difficult to fully suppress, the laws targeted the Catholic hierarchy and infrastructure. Catholic bishops, monks and friars were outlawed and subject to banishment or death if they returned. Building new Catholic churches was restricted.

Practical Effect: These measures aimed to decapitate the Catholic Church in Ireland and reduce its public presence, though a resilient underground network of clergy and worshippers continued to thrive.

The Structure of the "Protestant Ascendancy"

The Penal Laws were the framework upon which the Protestant Ascendancy was built and maintained. This term describes the privileged and dominant position of the minority Protestant population in Ireland, particularly those who were members of the established Church of Ireland, from the late 17th century until the Act of Union in 1801.

- Monopoly on Power: The Ascendancy held an almost absolute monopoly on political power, controlling the Irish Parliament, all major government offices, the judiciary and local administration. They were loyal to the British Crown, seeing their privileged position as inextricably linked to British authority.

- Economic Dominance: They owned the vast majority of the land, controlled commerce and dominated all lucrative professions, consolidating vast wealth and influence. This economic control reinforced their political and social supremacy.

- Social Hierarchy: The Ascendancy sat atop a rigidly defined social hierarchy. Below them were Dissenters, followed by the mass of the Catholic population, who were reduced to a largely landless, impoverished and disenfranchised peasantry or urban working class.

The Penal Laws and the Protestant Ascendancy created a deeply fractured society, characterised by systematic discrimination, economic exploitation and social injustice.

Grattan's Parliament and Irish Legislative Independence

The latter half of the 18th century saw a remarkable, albeit temporary, shift in the power dynamics between Ireland and Great Britain. While the Protestant Ascendancy firmly controlled Irish society, a strong movement for greater legislative autonomy emerged from within its own ranks. This era, famously associated with "Grattan's Parliament", saw Ireland achieve a significant degree of legislative independence in 1782, heavily influenced by the democratic ideals of the American and French Revolutions and powerfully backed by the rise of the Irish Volunteers.

The Call for Independence: Legislative Autonomy

For much of the 18th century, the Irish Parliament was severely circumscribed by British legislation. The Poynings' Law (1494) stipulated that no Irish parliamentary bill could be introduced without prior approval from the English Privy Council. Furthermore, the Declaratory Act of 1719 explicitly asserted the British Parliament's right to legislate for Ireland and declared that the Irish House of Lords had no appellate jurisdiction over Irish courts. These acts effectively ensured Irish parliamentary subservience to Westminster.

A growing movement, led by the orator and politician Henry Grattan, began to agitate for legislative freedom. Known as the Patriot Party, these Irish Protestant parliamentarians argued that Ireland was a distinct kingdom with its own parliament and should not be bound by British legislation. Their moment arrived in the context of Britain's military and political crises.

In 1782, seizing the opportunity presented by Britain's defeat in the American War of Independence and the threat of French invasion, Grattan's demands gained momentum. Under immense pressure, the British government repealed the Declaratory Act and amended Poynings' Law. This momentous achievement granted the Irish Parliament legislative independence: it could now initiate and pass its own laws without prior British approval. This period, from 1782 to 1800, is retrospectively known as "Grattan's Parliament".

Influence of American and French Ideals

The intellectual and revolutionary currents sweeping across the Atlantic and Europe dramatically influenced the Irish desire for greater autonomy:

- The American Revolution (1775-1783): The successful struggle of the American colonies against British imperial control provided a powerful template and inspiration. The American cry of "no taxation without representation" resonated deeply with those in Ireland who chafed under British legislative restrictions. The drain of British resources and military focus on the American war also created the opportune moment for Irish demands.

- The French Revolution (1789): The radical ideals of liberty, equality and fraternity, along with the overthrow of a monarchical system, further energised reform movements across Europe. For radical figures like Theobald Wolfe Tone, the French Revolution became a blueprint for a complete overhaul of Irish society and the establishment of a republic.

The Irish Volunteers

A critical factor in achieving legislative independence was the emergence of the Irish Volunteers. This was a Protestant militia movement that initially formed in 1778 to defend Ireland against potential French and Spanish invasion.

Composed of Protestant merchants, landowners and urban dwellers, the Volunteers quickly grew to some 80,000 - 100,000 armed and drilled men. While ostensibly for defence, they swiftly became a formidable political force. Under the leadership of figures like Henry Grattan, the Volunteers publicly passed resolutions supporting legislative independence and Catholic relief. Their existence as an armed, organised body outside official government control provided significant leverage. The British government, weakened by the American war and facing a potentially armed rebellion, found itself compelled to concede to the demands for legislative independence in 1782.

The Volunteers demonstrated that armed popular movements could achieve political aims, a lesson not lost on later, more radical groups like the United Irishmen.

"Grattan's Parliament" represented a significant period of Irish self-governance. However, its inherent limitations - its exclusively Protestant composition and its inability to fully control the executive - combined with the revolutionary ideals filtering from America and France, ultimately proved unsustainable. These factors would soon lead to more radical demands, the violent collapse of this limited autonomy in the 1798 Rebellion.

The Society of United Irishmen and the Path to Revolution

As the 18th century drew to a close, a new political movement emerged in Ireland, shaped by the revolutionary fervour of overseas rebellions. The Society of United Irishmen represented a bold departure from previous Irish political activism, openly challenging the sectarian divisions of the Protestant Ascendancy and advocating for a truly inclusive, republican Ireland. Their pursuit of religious equality and parliamentary reform, championed by key figures like Theobald Wolfe Tone and Lord Edward Fitzgerald, ultimately led them to seek French involvement in a bid to overthrow British rule.

Origins and Transformative Goals

The Society of United Irishmen was founded in Belfast in October 1791, primarily by Presbyterian radicals, quickly followed by a branch in Dublin. Their initial stated goals were:

- Religious Equality: To achieve complete Catholic emancipation, dismantling the Penal Laws and ending the established Church of Ireland's privilege. This was revolutionary, as it sought to unite all Irishmen, irrespective of creed, on a common political platform.

- Parliamentary Reform: To reform the deeply corrupt and unrepresentative Irish Parliament, replacing its borough-mongering and Anglican monopoly with a truly democratic system based on popular representation.

Inspired by the principles of the American and French Revolutions, the United Irishmen initially pursued constitutional methods. However, the British government's increasingly repressive measures, including the suppression of their societies, bans on political gatherings and the perceived inadequacy of the limited Catholic Relief Acts (which granted Catholics the vote but not the right to sit in Parliament), convinced them that peaceful reform was impossible.

By 1794, the United Irishmen largely transformed into a secret, revolutionary organisation dedicated to establishing an independent Irish Republic through armed rebellion, with French assistance. Their aim became to "substitute the common name of Irishman in place of the denominations of Protestant, Catholic and Dissenter".

Key Figures

The Society attracted a diverse array of intellectuals, radicals and aristocrats, united by their vision of a new Ireland:

- Theobald Wolfe Tone (1763-1798): Often considered the founding father of Irish republicanism, Wolfe Tone was a Protestant barrister from Dublin. A brilliant political theorist and strategist, he was the driving force behind the United Irishmen's move towards revolutionary republicanism and their pursuit of French aid. His writings, particularly An Argument on Behalf of the Catholics of Ireland, eloquently articulated the need for unity among all Irishmen. He believed that only a complete break from England could achieve genuine reform and equality.

- Lord Edward Fitzgerald (1763-1798): An aristocrat and military officer, Fitzgerald was the youngest son of the Duke of Leinster, Ireland's premier peer. He embraced radical republican ideals and joined the United Irishmen, becoming a key military leader. His high social standing and military experience made him an invaluable asset, though he was ultimately arrested shortly before the 1798 Rebellion, dying from his wounds in prison. His involvement underscored the Society's appeal across social strata.

Other prominent figures included Thomas Russell, James Napper Tandy and Robert Emmet (who would lead a later rebellion in 1803).

A Risky Alliance: French Involvement

Recognising that an internal uprising alone could not overcome British military might, the United Irishmen, under Wolfe Tone's persistent advocacy, sought substantial military assistance from revolutionary France.

- The Bantry Bay Expedition (1796): This was the most significant attempt at French intervention. A massive French fleet, carrying some 15,000 veteran troops, set sail for Bantry Bay in County Cork, with Wolfe Tone on board. However, adverse gales, poor seamanship and miscommunication plagued the expedition, preventing a landing. The fleet was ultimately forced to return to France, narrowly missing a potentially game-changing invasion.

The reliance on French military support highlighted the United Irishmen's understanding of their own limitations against a powerful British state. It also underscored the international dimension of the revolutionary era, where revolutionary ideals were often backed by military force across national borders. For the British, it confirmed their fears of a Franco-Irish alliance that could destabilise their empire.

Despite the failure at Bantry Bay, the United Irishmen continued to plan for a rising, buoyed by the hope of future French landings. The British government, aware of these contacts and the growing threat, intensified its repression in Ireland, leading directly to the 1798 Rebellion.

The 1798 Rebellion

In the closing years of the 18th century, Ireland was a society strained to its breaking point. The intellectual fervour of the American and French Revolutions found a ready audience in a land simmering with deep-seated grievances. This volatile mixture would soon erupt into one of the most violent and consequential episodes in the nation's history: the 1798 Rebellion.

The Seeds of Revolt

At the core of the rebellion's origins lay the political and economic marginalisation of the majority Catholic population and a significant portion of the Presbyterian community under the Anglican Protestant Ascendancy. The oppressive Penal Laws, though partially relaxed, still barred Catholics from positions of power and influence.

Inspired by revolutionary ideals of liberty and equality, the Society of United Irishmen was founded. Initially a constitutional reform group led by figures like Theobald Wolfe Tone, its goal was to unite "Protestant, Catholic and Dissenter" to achieve parliamentary reform. Frustrated by government intransigence and driven underground, the society evolved into a secret, revolutionary organisation aiming to establish an independent Irish republic.

The Uprising Unfolds and Is Crushed

The United Irishmen's plan for a coordinated national uprising was compromised from the outset by a network of government spies and informants. The arrest of much of the Leinster leadership in March 1798 crippled the command structure. Consequently, when the rebellion began on the night of 23rd of May, it manifested as a series of sporadic, localised and often desperate insurrections rather than a unified national campaign.

- Leinster: The most formidable rising occurred in County Wexford, where a populace, initially slow to mobilise, was goaded into action by the brutal counter-insurgency tactics of the local yeomanry and militia. Led by figures like the priest Father John Murphy, the Wexford rebels achieved stunning early victories at Oulart Hill and captured Enniscorthy and Wexford town. However, their advance was checked at New Ross and Arklow. The rebellion in Wexford was effectively broken at the climactic Battle of Vinegar Hill on the 21st of June, where a massive British force of around 13,000 soldiers overwhelmed the main rebel encampment.

- Ulster: The rebellion in the Presbyterian heartlands of Antrim and Down, where the United Irishmen had been strongest, was short-lived. Risings led by Henry Joy McCracken (Antrim) and Henry Munro (Down) were swiftly and ruthlessly put down at the battles of Antrim town and Ballynahinch.

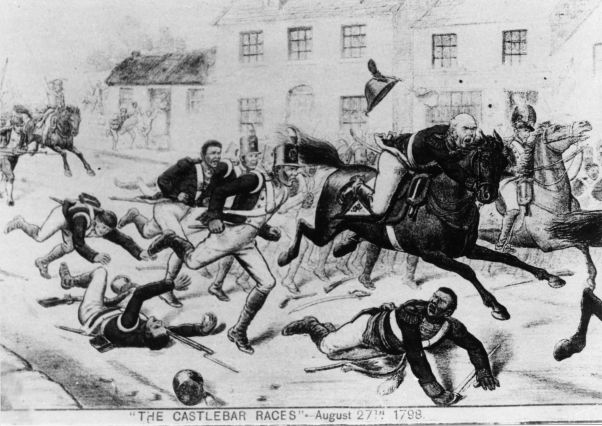

- French Intervention: In a belated and futile gesture, a French expeditionary force of around 1,100 soldiers landed at Killala Bay, County Mayo, in August. They achieved a remarkable victory over British forces at Castlebar (dubbed "The Races of Castlebar") but were ultimately surrounded and defeated at the Battle of Ballinamuck in County Longford on the 8th of September. A final French attempt to land a larger force, which included Wolfe Tone himself, was intercepted by the Royal Navy off the coast of Donegal. Wolfe Tone was captured and sentenced to hang, but he died in prison, likely by his own hand, cementing his status as a republican martyr.

Crucibles of Conflict and Cruelty

The year 1798 is remembered as much for its brutality as for its battles. The violence was ferocious on all sides, shattering the United Irishmen's ideal of a non-sectarian brotherhood.

- British Forces: Government troops, particularly the locally-recruited yeomanry and militia, engaged in a campaign of terror. Floggings, "pitch-capping" (where a cap of hot tar was applied to a suspect's head and then torn off), and summary executions were commonplace. Following the recapture of rebel-held areas, reprisal killings were widespread. One of the most infamous atrocities occurred at Gibbet Rath in Kildare, where hundreds of rebels who were attempting to surrender were massacred.

- Rebel Forces: The rebellion was also stained by sectarian atrocities. The most notorious incident was the Scullabogue Barn massacre, where between 100 and 200 loyalist prisoners, mostly Protestants, were murdered by panicked rebels fleeing the defeat at New Ross.

A Legacy Forged in Blood

The suppression of the rebellion was savage and absolute, with an estimated death toll ranging from 10,000 to 30,000. The immediate political consequence was the very thing the United Irishmen had fought to prevent: the complete absorption of Ireland into Great Britain. The British government, led by William Pitt, argued that only a full legislative union could guarantee stability. Despite significant opposition, the Irish Parliament was induced to vote itself out of existence, and the 1801 Act of Union was passed, creating the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

The failure of 1798 effectively ended the dream of a united, non-sectarian front against British rule for generations. It drove a wedge between the Protestant and Catholic traditions, with the memory of sectarian violence hardening identities.

Yet, the rebellion also created a powerful new pantheon of republican heroes and martyrs. The memory of Wolfe Tone and the "men of no property" who fought in '98 became a foundation for subsequent generations of Irish nationalists. It established the tradition of physical-force republicanism that would ring out through the 19th century and find its ultimate expression in the Easter Rising of 1916.

From Rebellion to Union

In the aftermath of the 1798 Rebellion, the political governance of Ireland was redefined. The fear of French ships on the Irish coast and the ferocity of the uprising sent a shockwave through the British establishment in London. Their conclusion: the centuries-old arrangement of a separate Irish Parliament, even one dominated by a loyal Protestant Ascendancy, was a strategic liability that could no longer be afforded. Thus, came its abolition and the creation of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland through the Acts of Union.

The Impetus for Union

The drive for a full legislative union came primarily from British strategic fear, not a desire for a harmonious partnership. The key reasons were:

- National Security: The 1798 Rebellion, with its direct appeal for and receipt of French military aid, confirmed London’s worst fears. Ireland was seen as the "back door" to Britain, a vulnerable flank that an enemy like Napoleonic France could exploit. For Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger, integrating Ireland directly under the singular authority of the Westminster Parliament was a geopolitical necessity.

- Political Control: Since achieving legislative independence in 1782, "Grattan's Parliament" had the potential to diverge from London on critical issues of trade and foreign policy. A union would eliminate this risk, centralising all decision-making in London.

- The “Catholic Question”: Pitt and his Chief Secretary for Ireland, Lord Castlereagh, believed that granting political rights to the Catholic majority was essential for long-term stability. They reasoned that within a wider United Kingdom, where Catholics would be a small minority, granting them the right to sit in Parliament would seem far less threatening. This was dangled as an implicit promise to win the support of the Catholic hierarchy.

Debate and Passage

The government's first attempt to pass a bill for union in 1799 was met with furious opposition and was defeated in the Irish House of Commons. Undeterred, Castlereagh and the Lord Lieutenant, Lord Cornwallis, embarked on a systematic and ruthless campaign to ensure victory on the second attempt. While the government presented principled arguments in pamphlets and sponsored articles, its real strategy was one of pure political coercion and inducement, a process memorably described by opponents as the work of "the purse and the bayonet".

The methods included:

- Patronage and Peerages: Titles, honours and powerful positions were liberally distributed to those who switched their vote to support the Union. Dozens of new peerages were created to pack the House of Lords and sway influential families.

- Direct Compensation: A sum of £1,260,000 (an astronomical figure at the time) was set aside to buy out the "owners" of parliamentary boroughs that would be disenfranchised by the Union. It was, in essence, a direct payment for the votes required.

- Purging the Opposition: Opponents of the Union holding government offices were summarily dismissed.

The anti-Union campaign was led with passion by figures like the Speaker of the House, John Foster, and the great orator Henry Grattan. Having retired from politics, Grattan had himself re-elected for the express purpose of fighting the bill. In a dramatic scene in January 1800, a frail and ailing Grattan, dressed in his old Volunteer uniform, entered the chamber at dawn to deliver a blistering two-hour speech against the "extinction" of Ireland. "The constitution may be for a time so lost", he declared, "the character of the country cannot be lost".

Despite these impassioned pleas, the combination of government pressure and immense patronage proved irresistible. The bill passed the Irish Commons in June 1800 by a vote of 158 to 115.

The End of a Parliament

The Acts of Union received royal assent in August 1800 and came into effect on the 1st of January, 1801. The Irish Parliament at College Green - a landmark of Dublin then as it is now - met for the last time. Its grand chambers were eventually sold to the Bank of Ireland.

The key terms stipulated that Ireland would be represented at Westminster by 100 MPs and 32 peers. Its economy was to be amalgamated with Britain's, and the Anglican Church of Ireland was formally united with the Church of England.

The promise of Catholic Emancipation was broken. King George III, citing his coronation oath to defend the Protestant faith, flatly refused to countenance the measure. Unable to deliver on his pledge, William Pitt resigned. This act of bad faith poisoned the Union from its inception. It ensured that the Catholic majority, who had been persuaded to remain neutral, now viewed the new arrangement as a sectarian settlement built on a lie.

The end of the Irish Parliament shifted the centre of Irish political life to London and set the stage for the great political struggles of the 19th century, from Daniel O'Connell's campaign for Catholic Emancipation to the long and arduous battle for the Union's repeal.

Sources & Further Reading

The information on this page is compiled from established archaeological and historical research. For detailed reading, please consult the following sources:

- Wikipedia: History of Ireland.

- Yale Macmillan Center: History of Penal Laws Against Irish Catholics.

- Wikipedia: Protestant Ascendancy.

- Wikipedia: Penal laws (Ireland).

- EBSCO Research Starters: Northern Star calls for Irish Independence.

- National Army Museum (NAM): Explore the Irish Rebellion of 1798.

- Wikipedia: Irish Rebellion of 1641.

- Britannica: Irish Rebellion (1798).

- Wikipedia: Penal laws (Ireland) - Second Reference.

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Penal Laws.

- Boston College: The Penal Laws in Ireland (Blog Post).

- UCLA Hibernian Metropolis: Penal Laws Against Irish Catholics.

- Ask About Ireland: 17th and 18th Century Education.

- Yale Macmillan Center: History of Penal Laws Against Irish Catholics (Second Reference).

- Oxford Reference: Authority Entry.

- The Idea of Irish History (Blog).

- OpenLearn: National Identity in Britain and Ireland 1780-1840.

- Legal Blog Ireland: The Irish Parliament.

- EBSCO Research Starters: Poynings' Law.

- EBSCO Research Starters: Henry Grattan.

- Cambridge History of Ireland: Politics of Protestant Ascendancy, 1730-1790.

- Museum of the American Revolution: The American Declaration of Independence in Ireland.

- EHNE: France, Ireland, Revolutionary Circulations.

- RANAM Journal: Article on Ireland and Europe.

- Wikipedia: Irish Volunteers (18th Century).

- Virtual Treasury of Ireland: Parliamentary Debate, 1782.

- The Irish Story: The Irish Volunteers of the Eighteenth Century.

- Causeway Coast and Glens: The Society of United Irishmen.

- Your Irish: The Society of United Irishmen.

- National Army Museum (NAM): Irish Rebellion 1798 (Second Reference).

- Ask About Ireland: Narrative Notes on the United Irishmen.

- Your Irish: The Society of United Irishmen (Third Reference).

- RANAM Journal: Article on Ireland and Europe (Second Reference).

- Dictionary of Irish Biography (DIB): Lord Edward Fitzgerald.

- Wikipedia: Lord Edward FitzGerald.

- UISSF: About Robert Emmet Day.

- Wikipedia: French expedition to Ireland (1796).

- Clyve Rose: An Irish Rebellion.

- Algo Education: Irish Independence Struggle.

- Pakenham, Thomas. The Year of Liberty: The Story of the Great Irish Rebellion of 1798.

- Elliott, Marianne. Partners in Revolution: The United Irishmen and France.

- Whelan, Kevin. The Tree of Liberty: Radicals, Catholicism and the Construction of Irish Identity, 1760-1830.

- Curtin, Nancy J. The United Irishmen: Popular Politics in Ulster and Dublin, 1791-1798.

- Foster, R. F. Modern Ireland: 1600-1972.

- Keogh, Dáire, and Nicholas Furlong, eds. The Mighty Wave: The 1798 Rebellion in Wexford.

- Bartlett, Thomas, and Dáire Keogh, eds. Rebellion: A Bicentenary Perspective.

- History Ireland Magazine.

- Virtual Treasury of Ireland: Rebellion Papers.

- The Irish Story.

- National 1798 Centre.

- National Army Museum (NAM): Irish Rebellion 1798 (Third Reference).

- Wikipedia: Irish Rebellion of 1798.

- UK Parliament: The Act of Union 1800.

- Visit Dublin: Henry Grattan.

- Anglican Communion: Church of Ireland.

- EBSCO Research Starters: Act of Union 1800.

- Ask About Ireland: Narrative Notes on the Act of Union.