Union and Famine

1801 AD – 1916 AD | Ireland as part of the United Kingdom, social change and the Great Famine.

A Century of Struggle

The long 19th century for Ireland began with the formal absorption of the island into a new United Kingdom and ended on the cusp of a revolution that would shatter it. This era, stretching from the legalism of the Act of Union to the fiery ideals of 1916, was defined by political struggle, unimaginable social trauma and a resilient national reawakening. It was the century that, more than any other, forged the identities and political fissures of the Ireland we know today.

The Union's Flawed Foundation

Upon its inauguration in 1801, the Union was presented by London as a solution to Irish instability. In reality, it began on a foundation of bitterness. The unfulfilled promise of Catholic Emancipation ensured that the majority population felt alienated from the new state from its inception. Political life became dominated by this single issue. The era produced Ireland’s first great democratic leader, Daniel O'Connell, who masterfully organised the Catholic masses into a powerful constitutional movement. His successful campaign for Emancipation (achieved in 1829) demonstrated the power of popular politics, but his subsequent movement to repeal the Act of Union ultimately failed, leaving the question of Irish governance unresolved.

A Famine of Unimaginable Proportions

This political struggle played out against a backdrop of social vulnerability. A rapidly growing population, particularly in the rural west, had become dangerously dependent on a single crop: the potato. When the blight struck in 1845, it caused a catastrophe of unimaginable proportions. The Great Famine (An Gorta Mór) was more than a simple food shortage; it was a societal collapse. Between 1845 and 1852, an estimated one million people died from starvation and disease and another million were forced to emigrate in "coffin ships". The government's response in London, constrained by a rigid ideology of laissez-faire economics, was tragically inadequate.

The Famine shattered rural society, decimated the Irish language and institutionalised emigration as a central feature of Irish life for the next century. The trauma and a deep-seated sense of grievance over the official response fundamentally changed the Irish political landscape.

Resurgence and Home Rule

In the post-Famine decades, Irish politics reorganised around two dominant goals: land reform and self-governance. The "Land War" of the late 19th century saw tenant farmers agitate against the landlord system, eventually leading to a series of Land Acts that enabled them to purchase their own farms. Simultaneously, the quest for self-government was revived under the banner of Home Rule, a movement that found its champion in the formidable parliamentary strategist Charles Stewart Parnell. His political dominance in the 1880s brought Ireland to the brink of achieving a devolved parliament within the UK.

Parnell’s downfall, combined with growing resistance to Home Rule from Ulster Unionists, created a political vacuum, which the Gaelic Revival quickly filled. Movements like the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) and the Gaelic League sought to reclaim Irish culture, language and identity. This cultural nationalism, combined with the persistent physical-force republicanism kept alive by groups like the Irish Republican Brotherhood, created a new generation of nationalists who were no longer content with the limited goal of Home Rule.

Catholic Emancipation: Daniel O'Connell and the Catholic Association

Daniel O'Connell, often hailed as "The Liberator", was a towering figure in 19th-century Irish political life. His campaigns for Catholic Emancipation and later for the repeal of the Act of Union reshaped Irish nationalism and demonstrated the power of mass political mobilisation.

Despite Ireland being overwhelmingly Catholic, a series of Penal Laws severely restricted the rights of Catholics. They were barred from holding public office, entering Parliament, serving in the military and even practicing law in certain capacities. The Act of Union in 1801, which merged the parliaments of Great Britain and Ireland, had promised some form of Catholic relief, but opposition prevented its immediate implementation.

Into this climate stepped O'Connell, a highly successful Catholic barrister from County Kerry. While rejecting the violent methods of the United Irishmen, he was an advocate for Catholic rights. In 1823, he co-founded the Catholic Association with Richard Lalor Sheil. This organisation proved to be a masterstroke of political innovation.

The Catholic Association was designed as a mass movement, funded by a "Catholic Rent" of a penny a month, which was collected through local priests. This low fee allowed even the poorest tenant farmers to contribute, drawing an unprecedented number of ordinary people into a national political campaign. The Association effectively mobilised the Catholic population, transforming it into a formidable political force. Through petitions, public meetings and grassroots organisation, O'Connell built huge pressure on the British government.

The climax of this campaign came in 1828 when O'Connell, still ineligible to sit in Parliament due to his Catholicism, stood for election in a by-election in County Clare. Despite the legal restrictions, he won by a landslide, creating a constitutional crisis: either Parliament would have to concede to Catholic Emancipation or risk widespread civil unrest in Ireland.

Catholic Relief Act of 1829

Faced with the prospect of rebellion and under pressure from Daniel O'Connell's popular movement, the British Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington, and his Home Secretary, Robert Peel (who had previously been a staunch opponent of Catholic rights), reluctantly concluded that Catholic Emancipation was necessary to avoid a violent uprising in Ireland.

The Catholic Relief Act of 1829 (also known as the Emancipation Act of 1829) was subsequently passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom. This landmark legislation removed most of the remaining significant legal restrictions on Catholics throughout the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Key provisions included:

- Right to sit in Parliament: Catholics were now permitted to take seats in both the House of Commons and the House of Lords.

- Access to public offices: Catholics could hold almost all civil and military offices, with a few exceptions.

- Entry to universities: Catholics gained access to universities from which they had previously been excluded.

However, the Act was not without its drawbacks from an Irish nationalist perspective. To appease hardline Protestants and minimise the immediate impact of the increased Catholic vote, the Act simultaneously raised the property qualification for voting in Irish county elections from 40 shillings to £10. This measure dramatically reduced the number of Irish voters, depriving many of the "forty-shilling freeholders", who had been instrumental in O'Connell's Clare victory, with the right to vote.

Despite this, the Act was a monumental achievement, largely credited to O'Connell's persistent and peaceful agitation. He became the first Catholic in modern history to take his seat in the House of Commons, earning his title "The Liberator".

The Repeal Association and "Monster Meetings"

Having achieved Catholic Emancipation, O'Connell turned his attention to his next great objective: the Repeal of the Act of Union. He believed that only an independent Irish Parliament could truly serve the interests of the Irish people. In 1840, he founded the Loyal National Repeal Association, again using the mass membership model of the Catholic Association, funded by a "Repeal Rent".

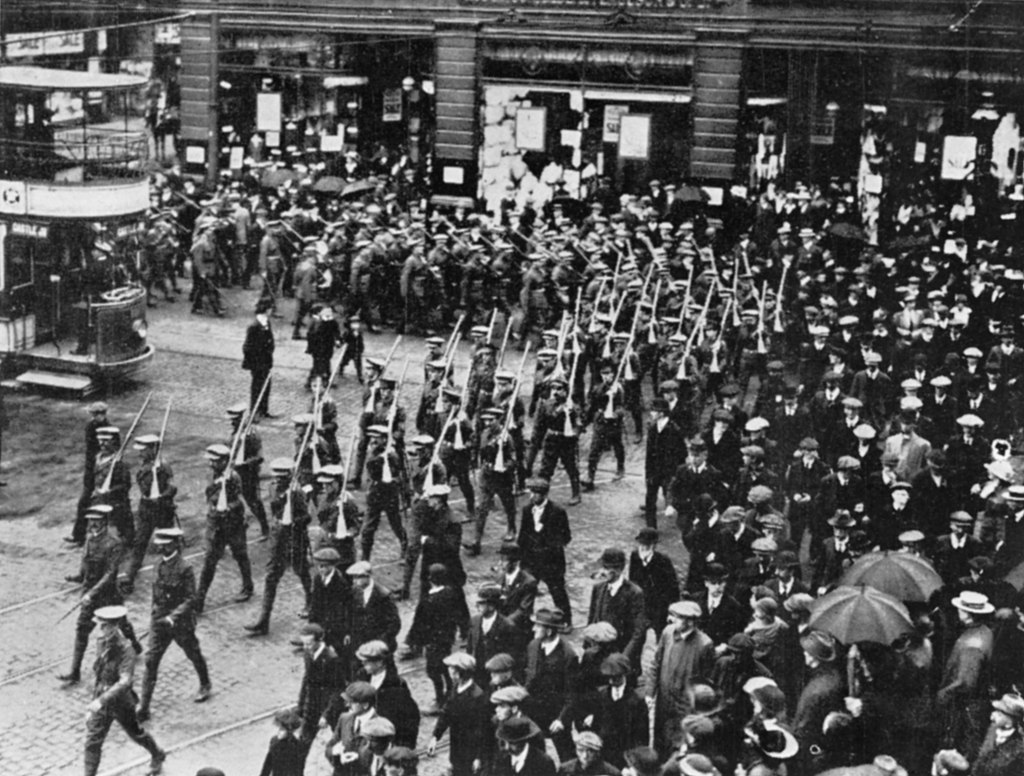

To demonstrate the overwhelming support for repeal and to exert pressure on the British government, O'Connell organised a series of huge outdoor rallies known as "Monster Meetings". These gatherings, primarily held throughout 1843 (which became known as "Repeal Year"), were unprecedented in their scale. Crowds numbering in the tens of thousands, sometimes estimated to be over a hundred thousand, would assemble at significant historical sites across Ireland, such as the Hill of Tara, Mullaghmast and Clontarf.

O'Connell would address these vast crowds, articulating his vision for a self-governing Ireland and detailing the economic and social benefits that repeal would bring. These meetings were meticulously organised, often involving elaborate processions with bands, banners and the active participation of the Catholic clergy. They were a powerful display of disciplined mass mobilisation, designed to show the British government that the Irish people were united in their demand for repeal, but committed to achieving it through peaceful, constitutional means.

The "Monster Meetings" reached their peak in 1843. However, the British government, under Prime Minister Robert Peel, became increasingly alarmed. When O'Connell planned a final, massive meeting at Clontarf in October 1843, the government issued a proclamation banning it and deployed a large military force. To avoid bloodshed, O'Connell reluctantly called off the meeting, a decision that, while preventing violence, also marked a turning point and a decline in the Repeal Association's momentum.

Despite O'Connell's subsequent arrest and conviction for conspiracy (a conviction later overturned on appeal), the Repeal movement ultimately failed to achieve its goal during his lifetime. Nevertheless, the "Monster Meetings" left their mark, demonstrating the potential for mass popular movements and cementing his place as one of the most significant figures in Irish history.

Emmet's Rebellion: A Brief, Failed Attempt at Independence

Emmet's Rebellion, though a short-lived and ultimately unsuccessful uprising, holds a significant place in the history of Irish nationalism. Led by the charismatic orator and radical United Irishman Robert Emmet, the rebellion on the 23rd of July, 1803, aimed to overthrow British rule in Ireland and establish an independent Irish republic. Its failure, however, cemented British control and led to a period of heightened repression, while also inspiring future generations of Irish republicans with a potent, albeit tragic, symbol of sacrifice for the cause of independence.

Background and Context

The 1798 Rebellion, a far larger and more widespread insurrection, had been brutally suppressed by British forces. Its aftermath saw the dissolution of the Irish Parliament and the implementation of the Act of Union in 1801, which formally incorporated Ireland into the United Kingdom. This move was deeply resented by many Irish Catholics and Dissenters, who felt their political autonomy had been stolen.

Robert Emmet, a Protestant nationalist from a wealthy Dublin family, had been involved in the United Irishmen movement prior to 1798. Exiled to France, he sought support from Napoleon Bonaparte for an invasion of Ireland. While in France, he also connected with other Irish exiles and continued to refine his revolutionary ideas.

Upon his return to Ireland in late 1802, Emmet found a country still simmering with discontent but also weary from the recent rebellion. He believed that the time was ripe for another attempt, particularly with Britain engaged in renewed hostilities with France. He began secretly organising, hoping to capitalise on a potential French invasion and widespread disaffection among the population.

The Plot and Preparations

Emmet's plan was audacious, if somewhat naive. He envisioned a coordinated uprising across Dublin and several provincial areas. The key objective was to seize Dublin Castle, the seat of British administration in Ireland, and other strategic points. He established a network of arms depots, secretly manufacturing pikes and explosives, and recruiting a small number of committed followers, primarily from the working class in Dublin.

However, Emmet's preparations were plagued by a lack of funds, insufficient numbers and significant security breaches. Informers were active and British authorities were aware of some revolutionary activity, though they underestimated the scale and imminence of Emmet's intended rising. A premature explosion at one of his arms depots in July 1803, which drew unwanted attention, forced Emmet to accelerate his plans.

The Rebellion

The chosen date for the uprising was Saturday, 23rd of July, 1803. Emmet had planned for several thousand men to converge on Dublin from various directions. However, the coordinated effort collapsed almost immediately. Miscommunication, fear of informers and a general lack of widespread support meant that only a few hundred men actually turned out.

Emmet, dressed in a green uniform, led the main body of rebels from their depot in Thomas Street. Their target was Dublin Castle. However, the march quickly devolved into chaos. Instead of a disciplined advance, the rebels became a disoriented mob. The limited number of British troops and yeomanry in the city were initially caught off guard but quickly regained control.

The most tragic event of the evening was the unprovoked murder of Arthur Wolfe, the Lord Chief Justice of Ireland, who was dragged from his carriage and piked to death by a group of rebels unrelated to Emmet's direct command. This act of brutality alienated public sympathy and provided the British authorities with a strong justification for harsh repression.

Realising the utter failure of the uprising, Emmet ordered his followers to disperse. He briefly went into hiding but was eventually captured on the 25th August, 1803, near Harold's Cross in Dublin.

Aftermath and Legacy

Emmet was tried for high treason on the 19th of September, 1803. His defense, eloquent and defiant, became legendary. In his famous speech from the dock, he refused to apologise for his actions, instead proclaiming his unwavering belief in Irish independence and expressing his hope that his epitaph would not be written "until my country takes her place among the nations of the Earth". He was found guilty and publicly executed by hanging and beheading on September 20, 1803, in Thomas Street, Dublin, the very location where his rebellion had begun.

Immediately following Emmet's Rebellion, the British government, wary of further unrest, implemented stringent security measures and intensified its efforts to suppress any signs of disloyalty. The United Irishmen movement, already weakened, was effectively crushed.

Emmet's sacrifice and his impassioned words resonated deeply with subsequent Irish nationalists. He became a martyr for the cause, a symbol of unwavering commitment to Irish freedom, regardless of the odds. His rebellion, despite its brevity and failure, served as a powerful reminder of the desire for independence among a segment of the Irish population. His legacy continued to inspire future revolutionary movements, from the Young Irelanders to the leaders of the 1916 Easter Rising, cementing his place as an icon in the long and turbulent struggle for Irish freedom.

The Great Famine: Hunger, Death and Emigration

The Great Famine, known in Irish as An Gorta Mór (The Great Hunger), was a catastrophic period in Irish history that profoundly reshaped the island's demographics, society, economy and national identity. Lasting roughly from 1845 to 1849, its impact was so significant that its effects are still felt today. A striking testament to its devastation is the fact that Ireland is one of the few countries in the world whose population is smaller today than it was in the mid-1800s. This is down to the starvation and mass emigration caused by An Gorta Mór.

Causes of the Great Famine

The Famine was not simply a natural disaster; it was a complex catastrophe exacerbated by a combination of natural phenomena, British government policy and pre-existing socio-economic conditions in Ireland.

- The Potato Blight:The immediate trigger for the famine was the arrival of Phytophthora infestans, a virulent fungus-like organism that causes potato blight. Potatoes had become the staple food for a huge portion of the Irish population, particularly the rural poor, who relied almost exclusively on them for sustenance. The blight first appeared in late 1845 and returned with even greater ferocity and consistency in subsequent years, leading to successive years of crop failure. This single-crop dependency meant that when the potatoes failed, there was no immediate alternative food source for millions.

- A Failed British Response:The response of the British government, initially under Robert Peel and later Lord John Russell, is a highly contentious aspect of the Famine. Russell's government was deeply committed to the economic doctrine of laissez-faire, which held that the market should be allowed to operate freely, with minimal government intervention, even in a time of crisis.

- Reluctance to interfere with food exports: While millions starved, large quantities of grain, livestock and other foodstuffs continued to be exported from Ireland to Britain, as the government refused to halt these exports or implement price controls.

- Reliance on public works: Relief efforts largely shifted from direct food aid to poorly managed public works schemes (e.g. road building). Starving people were forced to work for meager wages, often insufficient to buy food at inflated market prices.

- The Soup Kitchen Act and Rate-in-Aid: While temporary measures like the Soup Kitchen Act (1847) provided some relief, the later shift to making Irish poor rates solely responsible for famine relief (the "Rate-in-Aid" system) placed an impossible burden on already impoverished local communities, especially in the hardest-hit areas in the west.

- Evictions: Landlords, facing rising poor rates and tenant arrears due to crop failure, often resorted to mass evictions. The infamous "quarter-acre clause" of the Amended Poor Law of 1847 stipulated that anyone holding more than a quarter-acre of land was ineligible for outdoor relief, forcing many to surrender their land to qualify for aid, often leading to their eviction.

- Pre-existing Conditions: The famine occurred against a backdrop of deep-seated issues. An exploitative land tenure system meant most land was owned by Anglo-Irish absentee landlords, while tenants had no security and lived in extreme poverty. While the peasantry subsisted on potatoes, much of the country's fertile land was used to grow grain and raise livestock for export to Britain. This meant food was being produced in Ireland but was inaccessible to the starving majority. A rapidly growing, disproportionately poor rural population, paired with a weak industrial base, made the society vulnerable to any disruption in its food supply.

This meant:

The Human Cost: Death and Exodus

The human cost of the Great Famine was catastrophic.

- Death: It is estimated that at least 1 million people died from starvation and disease (such as typhus, cholera, dysentery and scurvy) that ravaged the weakened population. The death toll was highest in the western and southern counties, where dependence on the potato was greatest.

- Emigration: Another 1 to 2 million people emigrated from Ireland, primarily to the United States, Canada, Australia and Britain. This mass exodus began even during the worst years of the Famine, often on overcrowded and disease-ridden "coffin ships". Emigration continued for decades after the Famine, driven by poverty, lack of opportunity and the traumatic memory of An Gorta Mór.

Long-Term Consequences

The Great Famine left consequences that lasted for more than a century.

- Demographic Collapse: The population of Ireland plummeted from over 8 million in 1841 to about 4.4 million by 1911. This demographic decline was unique in Europe and continued for almost a century, largely due to continued emigration and declining birth rates.

- Land Consolidation and Agricultural Change: The Famine led to a radical transformation of the Irish agricultural landscape. Millions of smallholdings disappeared as landlords consolidated farms and converted land from tillage (crop growing) to pasture for cattle grazing, which was more profitable and required less labor. This contributed to further rural depopulation.

- Decline of the Irish Language: The Famine disproportionately affected the poorest and most Irish-speaking regions, particularly in the west. This contributed significantly to the decline of the Irish language as a vibrant community language.

- Deep-Seated Anguish and Anti-British Sentiment: The memory of the Famine fostered a sense of trauma, grievance and bitterness, particularly towards the British government, whose policies were seen as inadequate at best and genocidal at worst. This fueled Irish nationalism and radicalised many, leading to increased support for movements seeking complete independence from Britain.

- Social Transformation: The Famine hastened the decline of the traditional Irish rural community structure, accelerating social changes like later marriages and lower birth rates, as families became more cautious about supporting large numbers.

- Psychological Trauma: The Famine left a deep psychological scar on generations of Irish people, influencing their collective memory, cultural expressions and political aspirations.

The Irish Diaspora: A New Identity Abroad

The mass emigration during and after the Famine created a vast and influential Irish diaspora, particularly in the United States. The diaspora became a crucial source of remittances, sending money back to relatives in Ireland, which provided a lifeline for many struggling families. Organisations like the Fenian Brotherhood and later Clan na Gael drew heavily on Famine emigrants and their children, providing financial and sometimes military support for movements aimed at achieving Irish independence. They kept the memory of the Famine alive and ensured that its narrative, often critical of British rule, was propagated globally. While the Famine impacted the Irish language in Ireland, the diaspora sometimes played a role in preserving aspects of Irish culture and identity abroad.

In essence, the Great Famine was a pivotal moment that irrevocably changed Ireland, its people and its relationship with Britain, reverberating across continents and shaping the course of Irish history for over a century.

Land Agitation and Nationalism

In the period following the Great Famine, Ireland was characterised by intense land agitation and the rise of various forms of nationalism. These movements aimed to address the injustices of the land tenure system and to achieve greater political autonomy or even full independence from British rule.

Tenant Rights Movements

Even before the Famine, tenant farmers in Ireland faced severe insecurity. Most did not own the land they worked, holding it instead under precarious "at will" tenancies. Landlords could evict tenants for almost any reason, raise rents arbitrarily and tenants had no legal right to compensation for any improvements they made to their holdings. The Famine exposed the brutality of this system, leading to mass evictions and widespread suffering. In the wake of the Famine, various tenant rights movements emerged, demanding what became known as the "Three Fs":

- Fair Rent: Rents should be set by independent valuation, not by landlords.

- Fixity of Tenure: Tenants should have security of tenure as long as they paid their rent, preventing arbitrary eviction.

- Free Sale: Tenants should be able to sell the "goodwill" or improvements they had made to their holdings to an incoming tenant.

Early efforts, like the Tenant Right League (formed in 1850), had limited success. However, the pressure from these movements, combined with the increasing political awareness fostered by events like the Famine and Daniel O'Connell's campaigns, laid the groundwork for the more organised and successful land agitation that would follow.

Fenian Brotherhood / Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB)

In contrast to constitutional movements, the Fenian Brotherhood (in the United States) and its sister organisation, the Irish Republican Brotherhood (in Ireland), represented a more radical, physical force tradition of Irish nationalism. Founded in 1858, by Irish exiles John O'Mahony and Michael Doheny (Fenian Brotherhood) and James Stephens (IRB), these secret, oath-bound societies were dedicated to achieving an independent Irish Republic through armed rebellion. Many Fenians were veterans of the American Civil War or had been radicalised by the Famine. They believed that constitutional agitation was futile and that only force would dislodge British rule. They launched several attempts at insurrection, most notably the Fenian Rising of 1867 in Ireland and the Fenian Raids on Canada (1866-1871). While their military ventures largely failed, they demonstrated a continuing commitment to armed struggle and kept the flame of republicanism alive.

The Land League and Land Reform

The "Land War" (1879-1882), a period of intense agrarian agitation, was primarily led by the Irish National Land League. This powerful organisation was founded in 1879 by Michael Davitt, a former Fenian, alongside Charles Stewart Parnell. Davitt's own family had been evicted during the Famine and he passionately believed that land ownership was fundamental to Irish liberation.

The Land League's primary aim was to abolish landlordism and enable tenant farmers to own the land they worked. It employed a combination of mass mobilisation, direct action and parliamentary pressure:

- Mass Meetings: Drawing on O'Connell's "Monster Meeting" tradition, the Land League held huge rallies across Ireland, galvanising support and demonstrating the strength of popular discontent.

- Boycotts: The League popularised the tactic of "boycotting" (named after Captain Charles Boycott, a land agent who was ostracised by the community). This involved the complete social and economic isolation of landlords, agents or tenants who took over evicted farms.

- No-Rent Manifesto: At times, the League called for tenants to withhold rents to pressure landlords and the government.

The Land League successfully pushed the "Three Fs" into mainstream political discourse and forced the British government to act. Prime Minister William Gladstone responded with a series of Land Acts (most notably in 1881, which granted the "Three Fs"), culminating in the Wyndham Land Act of 1903. These acts facilitated land purchase by tenants through state loans, gradually transforming Ireland from a country of tenants into one of proprietors. This shift was a monumental victory for the Land League and fundamentally altered the social and economic fabric of rural Ireland.

Charles Stewart Parnell and the Home Rule Movement

Charles Stewart Parnell was arguably the most dominant figure in Irish politics in the late 19th century. A Protestant landlord from County Wicklow, he became the undisputed leader of the Irish nationalist movement. He skillfully combined the constitutional methods of parliamentary agitation with the extra-parliamentary force of the Land League.

Parnell became leader of the Home Rule League (which evolved into the Irish Parliamentary Party, IPP). The Home Rule movement sought to achieve a limited form of self-government for Ireland within the United Kingdom, with a devolved parliament in Dublin responsible for internal affairs, while Westminster retained control over imperial matters, defense and foreign policy.

Parnell's genius lay in his ability to:

- Discipline the Irish Party: He transformed the IPP into a highly disciplined, united political force in the House of Commons.

- Parliamentary Obstruction: He perfected the tactic of parliamentary obstruction, using procedural rules to delay British legislation and draw attention to Irish grievances.

- Alliance with Gladstone: His most significant achievement was securing the conversion of the Liberal Prime Minister William Gladstone to the cause of Home Rule. Gladstone introduced two Home Rule Bills (1886 and 1893), though both were defeated in Parliament, particularly by the House of Lords and a strong Unionist opposition.

Parnell's career ended in tragedy due to a divorce scandal in 1890, which split the Irish Party and significantly weakened the Home Rule movement. Despite this, his leadership had brought Home Rule closer to realisation than ever before.

Cultural Nationalism

Alongside the political and agrarian movements, a powerful wave of cultural nationalism emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This movement sought to revive and promote Irish language, literature, sports and arts, asserting an Irish identity distinct from British culture. It crucially underpinned political nationalism, arguing that Ireland was a nation through its unique cultural heritage, not just geography or grievance.

Key organisations and movements included:

- The Gaelic League (Conradh na Gaeilge): Founded in 1893 by Douglas Hyde and Eoin MacNeill, its primary aim was the "de-anglicisation of Ireland", specifically through the revival of the Irish language. It organised classes, published Irish-language literature and promoted traditional Irish music and dance. While often professing to be non-political, its emphasis on Irish identity inevitably spurred nationalist sentiment and many future revolutionary leaders were members.

- The Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA): Founded in 1884 by Michael Cusack and Maurice Davin, the GAA aimed to preserve and promote traditional Irish sports such as hurling and Gaelic football. The GAA rapidly became a hugely popular mass organisation, with clubs in almost every parish. Its "ban" on foreign games (especially soccer and rugby) among its members emphasised its nationalist ethos. Like the Gaelic League, it provided a powerful organisational network and instilled a sense of Irish identity and pride.

- The Abbey Theatre: Opened in Dublin in 1904, the Abbey Theatre became a cornerstone of the Irish Literary Revival. Led by figures such as W.B. Yeats, Lady Gregory and J.M. Synge, the Abbey aimed to create a distinctive Irish national theatre that drew on Irish myths, folklore and rural life. Plays often explored themes of Irish identity, history and the challenges of Irish society. While sometimes controversial (as with Synge's The Playboy of the Western World), the Abbey helped to create a vibrant national culture and provided a platform for Irish voices to express themselves artistically, often subtly challenging the prevailing British cultural hegemony.

These cultural movements, while diverse in their focus, collectively contributed to a powerful sense of national consciousness. They helped to articulate what it meant to be Irish beyond mere opposition to British rule.

Ulster Unionism: The Rise of a Counter-Movement

The rise of Irish nationalism, particularly the Home Rule movement, inadvertently sparked a counter-movement in the province of Ulster: Unionism. This distinct political identity, rooted in religious, economic and historical factors, became the most formidable obstacle to Irish self-government and ultimately led to the partition of Ireland.

Emergence of a Unionist Identity in Ulster

While there were Unionists throughout Ireland (mostly Protestants), the concentration and militancy of Unionism in Ulster set it apart. Several factors contributed to this:

- Religious Demography: The historical "Plantation of Ulster" in the 17th century had led to a significant influx of Protestant settlers from Scotland and England. By the 19th century, this had resulted in a Protestant majority in four of Ulster's nine counties (Antrim, Down, Armagh and Derry), and a substantial minority in others. This demographic reality fostered a deep-seated fear among these Protestants of becoming a minority within a Catholic-dominated, self-governing Ireland. The slogan "Home Rule is Rome Rule" encapsulated this fear of religious discrimination and loss of civil and religious liberties.

- Economic Prosperity and Industrialisation: Eastern Ulster, particularly Belfast and its surrounding areas, experienced rapid industrialisation in the 19th century, becoming a hub for shipbuilding, linen manufacturing and engineering. This economic prosperity was deeply integrated with the British industrial economy. Unionists feared that Home Rule would lead to protectionist policies, higher taxes and a decline in trade with Britain, jeopardising their economy. They saw their prosperity as a direct benefit of the Union and feared that an independent Dublin parliament would be dominated by agricultural interests and less concerned with Ulster's industrial needs.

- Loyalty to the British Crown: Many Ulster Protestants felt a strong sense of British identity and loyalty to the British Empire. They viewed themselves as integral parts of the United Kingdom, not as a stand-alone Irish nation aiming for self-rule. Their historical narrative emphasised their connection to the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and King William III (William of Orange), victories that secured Protestant ascendancy.

As the threat of Home Rule grew, diverse Protestant political factions, including traditionally Liberal Presbyterians and more Conservative Anglicans (often associated with the Orange Order), coalesced into a unified Unionist political force. This broad alliance transcended previous internal divisions to present a united front against Home Rule.

Resistance to Home Rule

Unionist resistance to Home Rule intensified with each successive Home Rule Bill introduced in Westminster (1886, 1893, and particularly 1912). They argued vehemently that:

- Self-determination for Ulster: While Irish nationalists argued for self-determination for the whole of Ireland, Unionists countered that the Protestant majority in Ulster had an equal right to self-determination and to remain within the United Kingdom.

- Economic Ruin: They predicted economic disaster for Ulster's industries under a Dublin parliament.

- Religious Persecution: They expressed deep fears of discrimination and persecution under a Catholic-dominated government.

- Imperial Disintegration: They saw Home Rule as the thin end of the wedge, an initial step towards complete separation from Britain, which they opposed on both ideological and practical grounds.

Leading this resistance were charismatic figures such as Sir Edward Carson, a Dublin-born barrister who became the leader of the Irish Unionist Alliance, and James Craig, a prominent Ulster industrialist. They orchestrated a highly effective and militant campaign of opposition.

A pivotal moment in this resistance was Ulster Day, 28th of September, 1912, when over 500,000 men and women signed the Ulster Covenant (men) and the "Declaration" (women). This solemn pledge vowed to "use all means which may be found necessary to defeat the present conspiracy to set up a Home Rule Parliament in Ireland" and, if Home Rule were imposed, to "refuse to recognise its authority." This act was a clear declaration of intent to resist by force if necessary.

The Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

The ultimate expression of Unionist resistance to Home Rule was the formation of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), often referred to as "Carson's Army".

- Formation (1912-1913): As the Third Home Rule Bill progressed through Westminster, Ulster Unionists began to openly drill and organise paramilitary units. In January 1913, these militias were formally consolidated into the UVF, with the stated purpose of resisting the imposition of Home Rule on Ulster by force of arms. Recruitment was limited to those who had signed the Ulster Covenant, with a target strength of 100,000 men, many of whom were ex-soldiers or had received military training.

- Arms Smuggling: In a daring operation known as the Larne gun-running in April 1914, the UVF successfully smuggled some 20,000 rifles and millions of rounds of ammunition from Germany into Ulster. This act, carried out with remarkable efficiency and a degree of tacit support from elements within the British establishment (including some army officers, as demonstrated by the Curragh Mutiny), showed the serious intent and capability of the UVF.

- Political Impact: The formation and arming of the UVF created an unprecedented constitutional crisis, bringing Britain to the brink of civil war. It demonstrated that Ulster Unionists were prepared to use violence to prevent Home Rule. The UVF's actions also directly inspired Irish nationalists to form their own paramilitary force, the Irish Volunteers, to ensure that Home Rule would be implemented.

The outbreak of World War I in August 1914 temporarily defused the Home Rule Crisis, as the implementation of the Third Home Rule Bill was suspended until the war's end. Many UVF members joined the British Army, forming the core of the 36th (Ulster) Division, which suffered horrific casualties at the Somme battles. However, the UVF's existence, its defiance and its military preparations had changed the "Ulster Question" from a political debate into a potential armed conflict, setting the stage for the eventual partition of Ireland.

Sources & Further Reading

The information on this page is compiled from established archaeological and historical research. For detailed reading, please consult the following sources:

- ThoughtCo: Irish History: The 1800s.

- UK Parliament: Catholic Emancipation.

- Wikipedia: Great Famine (Ireland).

- Economics Observatory: The Great Irish Famine: What are the lessons for policymakers today?

- UK Parliament: The Great Famine.

- Richmond Barracks: History of Richmond Barracks.

- Mayo.ie: The Great Famine.

- The Irish Potato Famine: Famine in Ireland.

- Wikipedia: Irish National Land League.

- EBSCO Research Starters: Irish Home Rule Debate.

- Wikipedia: Gaelic Athletic Association.

- Ask About Ireland: Robert Emmet - After the Insurrection.

- The Irish Story: Robert Emmet: The 1803 Proclamation of Independence and the Ghost of 1798.

- National Library of Ireland: Robert Emmet Sources.

- Virtual Treasury: TNA-HO-100-113-203.

- National Archives of Ireland: The Rebellion Papers.

- Virtual Treasury: PUB-LAW-1803-OyerTerminer.

- Ricorso: Anne Devlin Life.

- Kilmainham Gaol: Remembering Anne Devlin 2021.

- Irish Academic Press: Robert Emmet and the Rebellion of 1798 Vol. 1.

- Fordham University: O'Connell's Address to the People of Ireland (1836).

- Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics: Daniel O'Connell.

- Yale Macmillan Center: History of Penal Laws Against Irish Catholics.

- NatWest Group Heritage: Daniel O'Connell.

- Museum of the American Revolution: Daniel O'Connell.

- Dictionary of Irish Biography: Richard Lalor Sheil.

- EBSCO Research Starters: Roman Catholic Emancipation.

- Wikipedia: Catholic Rent.

- EBSCO Research Starters: Daniel O'Connell.

- Dictionary of Irish Biography: Daniel O'Connell.

- UK Parliament: 1829 Catholic Emancipation Act.

- Wikipedia: Daniel O'Connell.

- Britannica Kids: Daniel O'Connell.

- ThoughtCo: Ireland's Repeal Movement.

- Cambridge Core: Repeal Year in Ireland: An Economic Reassessment.

- Libertarianism.org: Passionate Oratory: A Biography of Daniel O'Connell.

- Birkbeck University: The Great Famine and its Aftermath.

- Fenians.org: The Fenian Brotherhood.

- Britannica: Great Famine (Irish history).

- President of Ireland: Reflecting on An Gorta Mór.

- PMC NCBI: The Great Irish Famine.

- Irish Great Hunger Museum: Learn.

- University of Cambridge: Whose fault is famine?

- The Cricket Bat That Died For Ireland: Indian Meal Ticket.

- USC Scalar: Russell's Administration and the Irish Famine.

- UK Parliament: The Great Famine - Relief Commission.

- Irish Echo: The truth behind the Irish Famine.

- Maynooth University: Wreckers and levellers: evicting Ireland's poor during the Great Famine.

- Oughterard Heritage: The administration of the Poor Law.

- Wikipedia: Great Famine (Ireland) - Woodham-Smith.

- USC Scalar: Logistics of Coffin Ships.

- Fiveable: Potato Famine - Social and Economic Impacts.

- Cambridge Core: Cultural Effects of the Famine.

- Library of Congress: Irish Catholic Immigration to America.

- Wikipedia: Irish diaspora.

- National Museum of Ireland: Irish Emigration to America.

- Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia: The Irish and Ireland.

- MIMMOC Journals: The Fenian Brotherhood in the 19th Century.

- J. Pellegrino: The Land League.

- Wikipedia: Free sale, fixity of tenure, and fair rent.

- Medium: The Irish Land Wars.

- Wikipedia: Land War.

- Case Western Reserve University: Irish Nationalism in Cleveland.

- Dictionary of Irish Biography: John O'Mahony.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia: Fenian Raids.

- EBSCO Research Starters: Fenian Risings.

- Ask About Ireland: The Land League Crisis.

- DotNews: Family Trauma Then 1850 and Now.

- Britannica Kids: Land League.

- EBSCO Research Starters: Irish Tenant Farmers Stage First Boycott.

- Britannica: Land League.

- University of Galway: Land Acts (Appendix).

- Wikipedia: Land Acts (Ireland).

- Britannica: Charles Stewart Parnell.

- University of Delaware Library: Parnell.

- EBSCO Research Starters: Ireland Granted Home Rule.

- Wikipedia: Charles Stewart Parnell.

- UK Parliament: Two Home Rule Bills.

- National Portrait Gallery: Charles Stewart Parnell.

- National Army Museum: Irish War of Independence.

- Medium: The GAA: How Gaelic Games Shaped Irish Nationalism.

- Stichting Argus: Fenian.

- American Repertory Theater: About The Abbey Theatre.

- Abbey Theatre: History.

- EBSCO Research Starters: Abbey Theatre Heralds Celtic Revival.

- Wikipedia: Unionism in Ireland.

- Wikipedia: Unionism in the United Kingdom.

- Discover Ulster-Scots: The Story of the Presbyterians in Ulster.

- CAIN: Sectarianism - Brewer.

- Wikipedia: Economic history of Ireland.

- Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique: Ulster Unionism.

- CAIN: The Formation of the Northern Ireland State.

- English Historical Review: Review of 'Ulster Presbyterians and the Irish Language'.

- National Museum of Ireland: Asgard Yacht and Home Rule Crisis.

- CAIN: The Ulster Question.

- Wikipedia: Home Rule Crisis.

- UK Parliament: James Craig (1871-1940).

- NIDirect: About the Ulster Covenant.

- EBSCO Research Starters: Irish Home Rule Bill.

- 1914-1918 Online: Pre-war Paramilitary Mobilisation.

- Irish Volunteers: Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF).

- NI Assembly: Covenant Lecture.

- Imperial War Museums: Battle of the Somme.

- Wikipedia: History of Ireland.

- Wikipedia: Protestant Ascendancy.

- Wikipedia: Penal laws (Ireland).

- EBSCO Research Starters: Northern Star calls for Irish Independence.

- National Army Museum (NAM): Explore the Irish Rebellion of 1798.

- Wikipedia: Irish Rebellion of 1641.

- Britannica: Irish Rebellion (1798).

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Penal Laws.

- Boston College: The Penal Laws in Ireland (Blog Post).

- UCLA Hibernian Metropolis: Penal Laws Against Irish Catholics.

- Ask About Ireland: 17th and 18th Century Education.

- Oxford Reference: Authority Entry.

- The Idea of Irish History (Blog).

- OpenLearn: National Identity in Britain and Ireland 1780-1840.

- Legal Blog Ireland: The Irish Parliament.

- EBSCO Research Starters: Poynings' Law.

- EBSCO Research Starters: Henry Grattan.

- Cambridge History of Ireland: Politics of Protestant Ascendancy, 1730-1790.

- Museum of the American Revolution: The American Declaration of Independence in Ireland.

- EHNE: France, Ireland, Revolutionary Circulations.

- RANAM Journal: Article on Ireland and Europe.

- Wikipedia: Irish Volunteers (18th Century).

- Virtual Treasury of Ireland: Parliamentary Debate, 1782.

- The Irish Story: The Irish Volunteers of the Eighteenth Century.

- Causeway Coast and Glens: The Society of United Irishmen.

- Your Irish: The Society of United Irishmen.

- Wikipedia: Lord Edward FitzGerald.

- Dictionary of Irish Biography (DIB): Lord Edward Fitzgerald.

- UISSF: About Robert Emmet Day.

- Wikipedia: French expedition to Ireland (1796).

- Clyve Rose: An Irish Rebellion.

- Algo Education: Irish Independence Struggle.

- Pakenham, Thomas. The Year of Liberty: The Story of the Great Irish Rebellion of 1798.

- Elliott, Marianne. Partners in Revolution: The United Irishmen and France.

- Whelan, Kevin. The Tree of Liberty: Radicals, Catholicism and the Construction of Irish Identity, 1760-1830.

- Curtin, Nancy J. The United Irishmen: Popular Politics in Ulster and Dublin, 1791-1798.

- Foster, R. F. Modern Ireland: 1600-1972.

- Keogh, Dáire, and Nicholas Furlong, eds. The Mighty Wave: The 1798 Rebellion in Wexford.

- Bartlett, Thomas, and Dáire Keogh, eds. Rebellion: A Bicentenary Perspective.

- History Ireland Magazine.

- Virtual Treasury of Ireland: Rebellion Papers.

- The Irish Story.

- National 1798 Centre.

- UK Parliament: The Act of Union 1800.

- Visit Dublin: Henry Grattan.

- Anglican Communion: Church of Ireland.

- EBSCO Research Starters: Act of Union 1800.

- Ask About Ireland: Narrative Notes on the Act of Union.